Retail Targeted Campaigns—Domain Fraud, Brand Impersonation, and Ponzi Schemes, oh my!

Share this entry

Threat Actors Shopping Around Domain Fraud, Brand Impersonation, and Ponzi Schemes

It’s hard to overstate the significance of the retail sector on a global level; it’s a driver of countless types of economic activity. Shipping and transportation, manufacturing, technology, commercial real estate, finance, and so many other sectors benefit from the flow of goods and services it generates. Estimated to be over $30 trillion globally annually, the top 50 retailers alone generated over $1.13 trillion in revenue in 2023.

From the most significant global corporations to the neighborhood corner stores and millions of online shops, the sector’s scope and diversity are truly enormous.

Given the volumes of goods and services and their monetary value, the retail sector is no stranger to the subjects of fraud, theft, and other types of crime. Threat actors have always been and continue to actively engage in efforts to benefit from the value the industry creates illicitly. Beyond the monetary losses, this drives the impact on an organization’s brand, and the relationship with their consumer is equally important. The threat landscape has expanded as the industry has sought to embrace new online models for reaching consumers globally.

This blog highlights several ways that actors seek to take advantage of this growing landscape and aid in understanding how such activity can be enumerated and “clustered” to help organizations defend themselves. As such, we will dig into three different “clusters” affecting the retail sector.

Cluster One – E-commerce Domain Fraud

As the retail sector sought to respond to the challenges brought on by the global pandemic and transition even more fully to e-commerce solutions, threat actors also adapted their tactics. While many retailers managed this transition, the impact on others led to an increase in the closure of physical storefronts and, in turn, an increase from threat actors in “outlet store” and “store closing” types of fraud. Trying to lure victims with the promise of significant discounts, one threat actor group stood up hundreds of websites seeking to impersonate dozens of global retailers and consumer brands. Let’s look into what this group did in more detail.

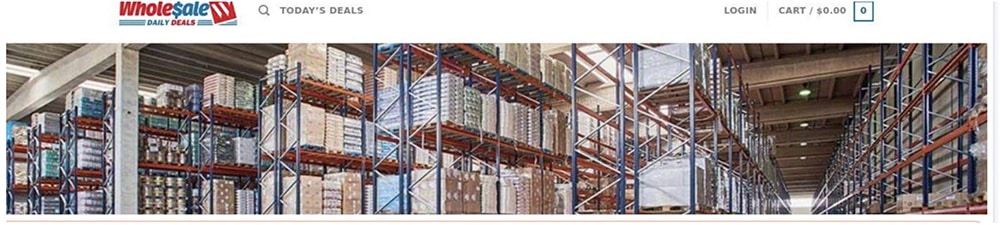

As shown in Figure 1, screenshots in DomainTools Iris Investigate show happed[.]shop impersonated multiple brands over short periods of time, often changing between victims in a matter of days or weeks. This was only one of several domains used in the campaign.

To facilitate the impersonation of so many brands, the actor relied on templates which provide defenders an additional method of enumerating potentially offending domains. The actor was consistent in their use of certain domain registrars, common name servers, and services like Cloudflare in order to manage and obfuscate their campaigns. This fingerprint combination allowed for the identification of hundreds of additional domains.

The use of templates and redirecting domains to each other also afforded opportunities to identify missteps in their campaigns. One such domain that appeared in numerous templates related to other brands was nordstrom-rack-dream[.]com which was found on a template that was related to discountedca[.]com. By examining redirections, we discovered additional IP addresses, including 3.33.208[.]165 and 15.197.242[.]87. Viewing passive DNS results uncovered close to 5,000 additional domains impacting dozens of other brands.

The actors would often repurpose a domain and use it to abuse many different brands often within days of each other. The domain we covered in our blog about usgirlshop[.]com is just one example about how using all parts of the Whois record and searching through Iris for historical screenshots opened up significant new avenues for investigation. The domain registration details included a very unique address from which to pivot off of. This address was associated with five other domains including one that impersonated Steve Madden shoes and another that sought to represent American Threads, a popular clothing retailer. To use “usgirl” as an example, just 8 days before targeting American Girl, it was impersonating a furniture retailer as seen here, and another domain that featured the furniture retailer went on to impersonate yet another shoe retailer, as shown in Figure 2.

What was consistent amongst the thousands of domains were the website templates used. Understanding the potential source of the template was important in fingerprinting domains that cluster together. Thankfully the TLS/SSL cert data related to a number of domains provided a key piece of intelligence. Given the scale at which this actor group operates, they tended to reuse TLS/SSL certs. Running across individual certs that had 40 or 50 domains was not unusual. One certificate stood out head and shoulders above the others, with over 2,300 domains associated with it. Looking at the cert data there was a domain associated with it that was unlike the domains associated with brand impersonations. Reviewing that domain revealed the source of the templates used in so many attacks. The actors were abusing a legitimate e-commerce platform designed and intended for legitimate brands and companies to launch their own online stores. The threat actor generated thousands of landing pages for their malicious domain registrations using an automated process from a number of potential templates. The abuse of the platform also provided a key insight into Facebook and other ads that promoted the fraudulent domains to potential victims. The actors took advantage of marketing tools meant for legitimate purposes to further drive traffic to these sites through the integrations offered by the platform.

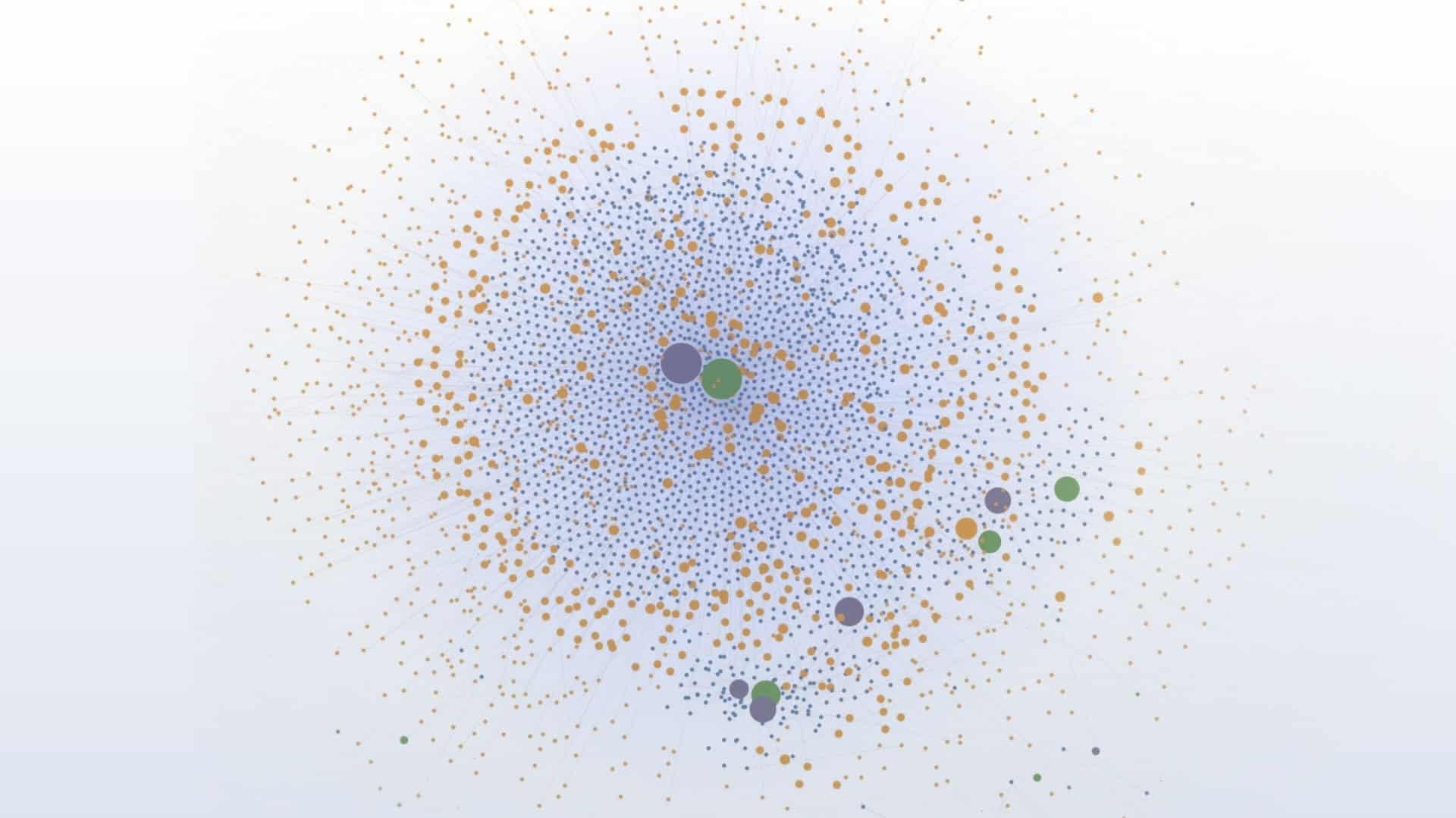

Using the fingerprint of registrar preference, Cloudflare service, and template image, along with their preference for TLDs like .shop, .store, and .com, we could finally see the full extent of their campaigns see Figure 3. The toll in domains, as mentioned previously, is in the thousands over the past three years alone, and impacted hundreds of brands, including the largest global retailers, luxury brands like Rolex and Cartier, telecommunications providers, clothing stores, and yes, even American Girl.

Cluster Two – Brand Impersonation for Financial Fraud

The Internet has enabled many people to make money working remotely. Unfortunately, bad actors have also leveraged the notion of “side hustles” to enrich themselves with schemes to lure individuals looking for extra income. Promised payments for completing tasks or recruiting others are two examples of how actors try and leverage their activities by preying on both sides of the economic spectrum. They do this by using brand reputation and goodwill associated with well-known retailers to conduct financial fraud.

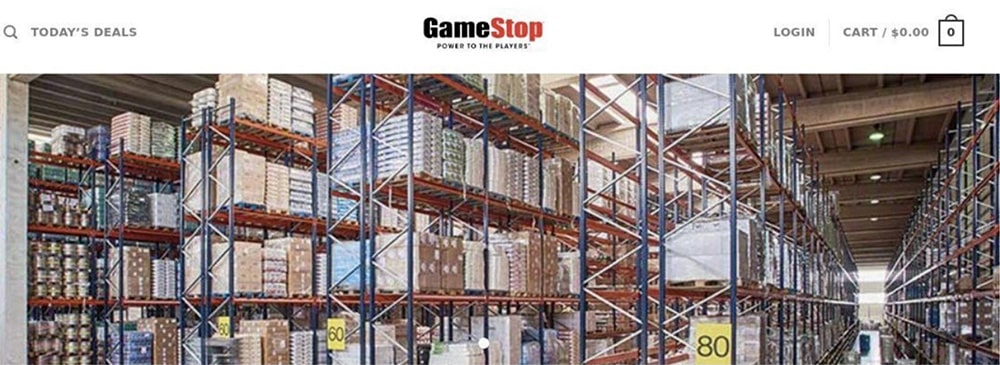

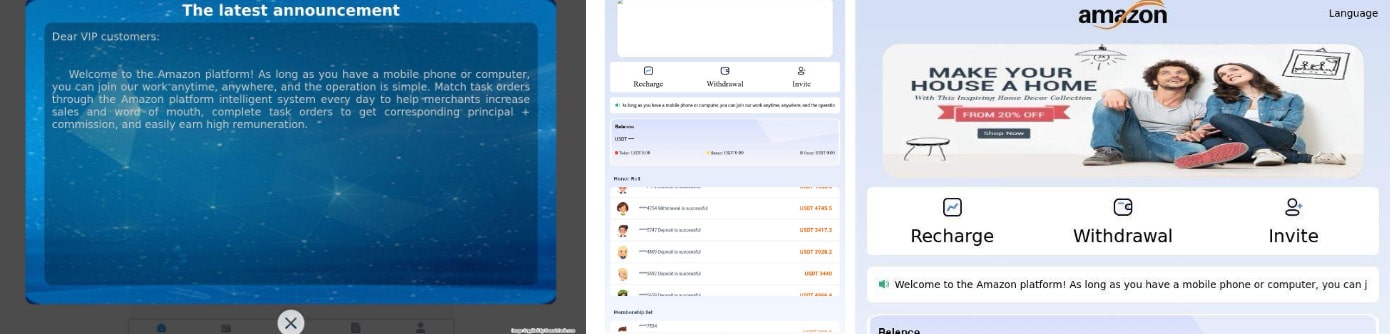

This activity cluster started with amazon-9000[.]com, which we found in February 2024, via an Iris Detect alert using the term “Amazon” as a trigger for new domain registrations. The domain was privacy-protected and used Cloudflare to obfuscate the IP that it resolved to. Undeterred, we pivoted on the Google Analytics code associated with the website. The code revealed over two hundred other domains. Upon examination, an overwhelming number related to Amazon including, amazon-300[.]com, amazon-2000[.]com and many others following similar registration conventions. Reviewing the domains and screenshots associated with them revealed a common set of landing pages, a few of which are shown in Figure 4.

The copy text in Figure 4 reads: “Welcome to the Amazon platform! As long as you have a mobile phone or computer, you can join our work anytime, anywhere, and the operation is simple. Match task orders through the Amazon platform intelligent system every day to help merchants increase sales and word of mouth, complete task orders to get corresponding principal + commission, and easily earn high remuneration.”

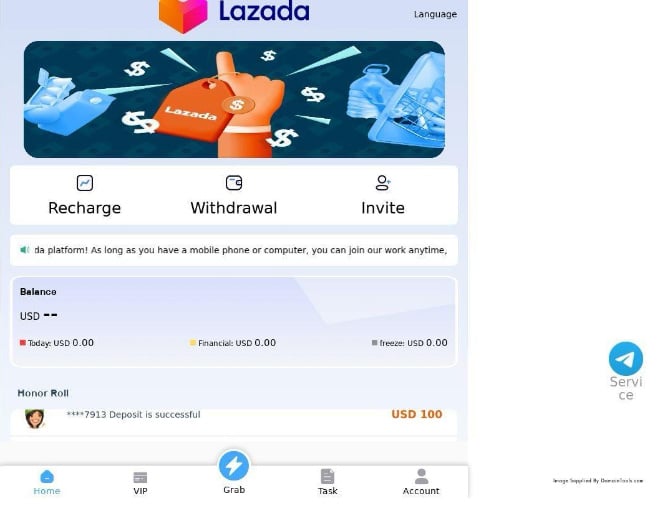

We used URLScan to look closer at amazon-9000[.]com. The HTTP requests revealed one file that caught our eye, “Calculate-revenue.png.” This file called out to 107.148.90[.]74, which in turn was hosting other Amazon spoof domains, including amazon-labor[.]com. The scope of the investigation quickly expanded to include “awsa” as an Amazon-related theme, and it went on to include many other brands including, Allegro, Target, Lazada, Ebay, NewEgg, Aliexpress, TikTok, and Walmart. Naming conventions for all these brand domains closely followed those first observed with Amazon (i.e. using numbers) and the templated screenshots.

One specific example highlighted in Figure 5 is of a Lazada domain which shared similarities with both the Amazon and Target domains. Beyond the shared naming convention islazada-111[.]com, we found the TLS/SSL certificate associated with it (with a hash of 8965ad719ebeffc18718656d965f389d43627f6e), included 18 other Lazada-themed domains. This pivot via a shared certificate was a trait we more broadly found, a certificate to link domains affecting a single brand.

There is also a Telegram logo in the right corner of each screenshot, labeled “Service.” It links to Telegram channels named to be associated with the brand they are impersonating. The shift to Telegram allows the actors to further communicate with prospective victims and interview them about country of origin and other questions. It’s also used to attempt to explain what the “platform” is and how they supposedly support the aims and business units of the brand they are impersonating. Figure 6 shows a screenshot of an interaction with one such channel.

Once a victim has registered, they are informed that they must “invest” USDT (“Tether”) cryptocurrency with the group in order to receive tasks and the associated “commissions” that go with them. Starting at $20 in USDT and scaling up to $1,000 USDT, commission rates jump with promised returns of up to $20,000 USDT. Beyond the “pig butchering” aspect of this offer with the promise of enormous gains, there is a heavy emphasis on a second facet of their scheme to encourage the user to recruit others. The actors provide the victim with what might seem like a multi-level marketing opportunity, but would be more accurately characterized as what it is: a Ponzi scheme.

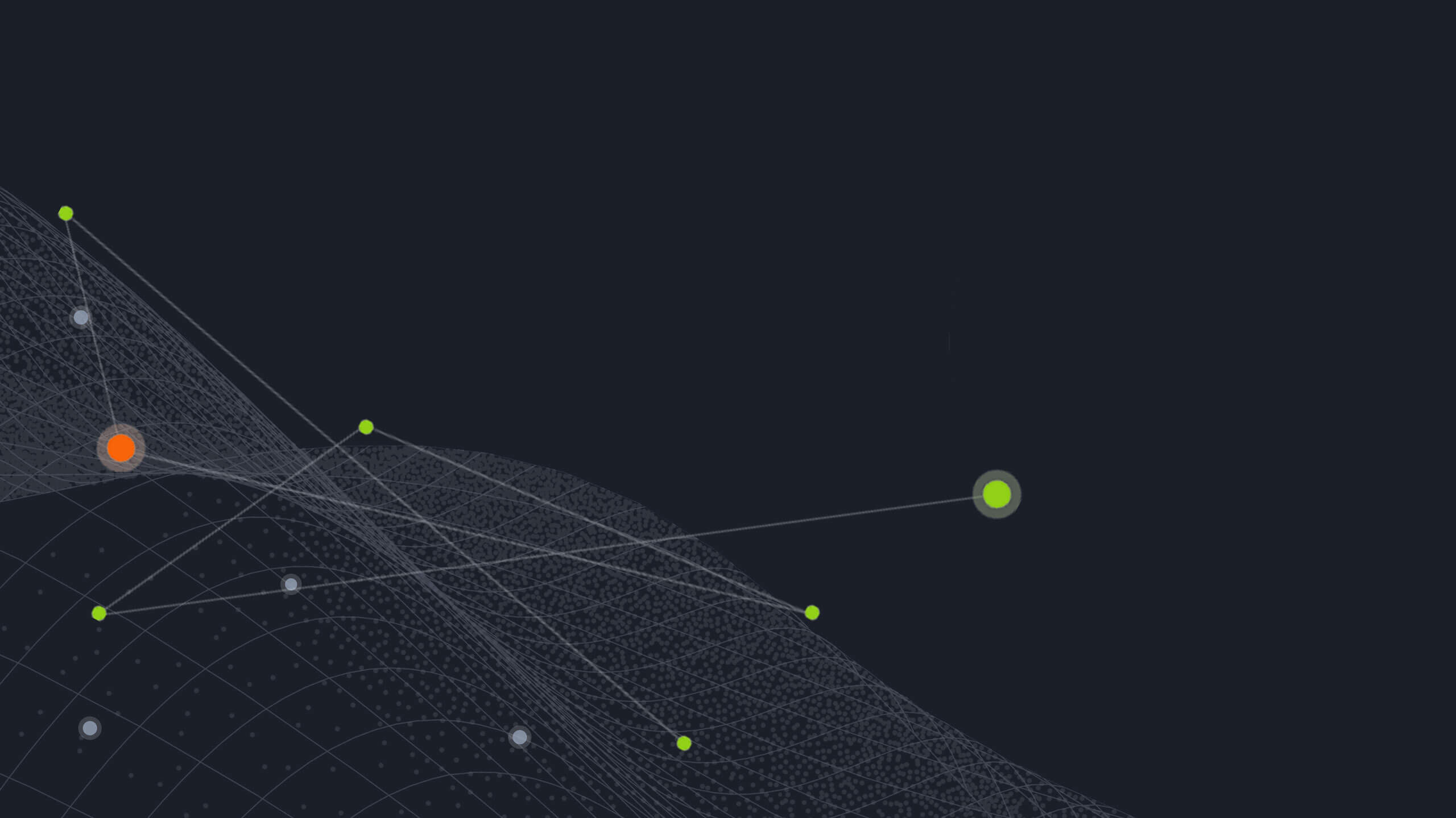

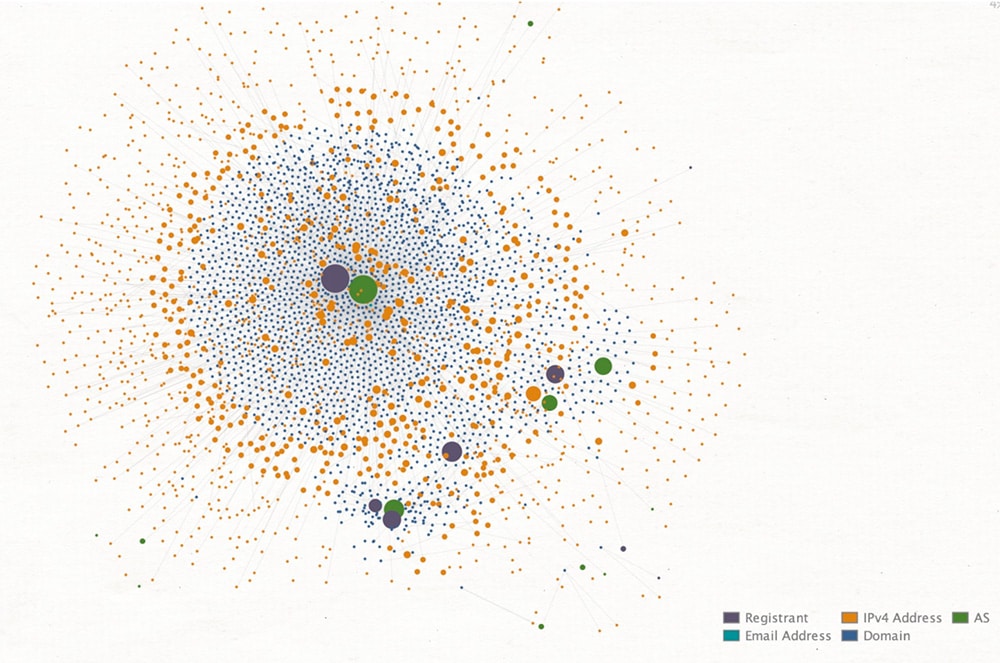

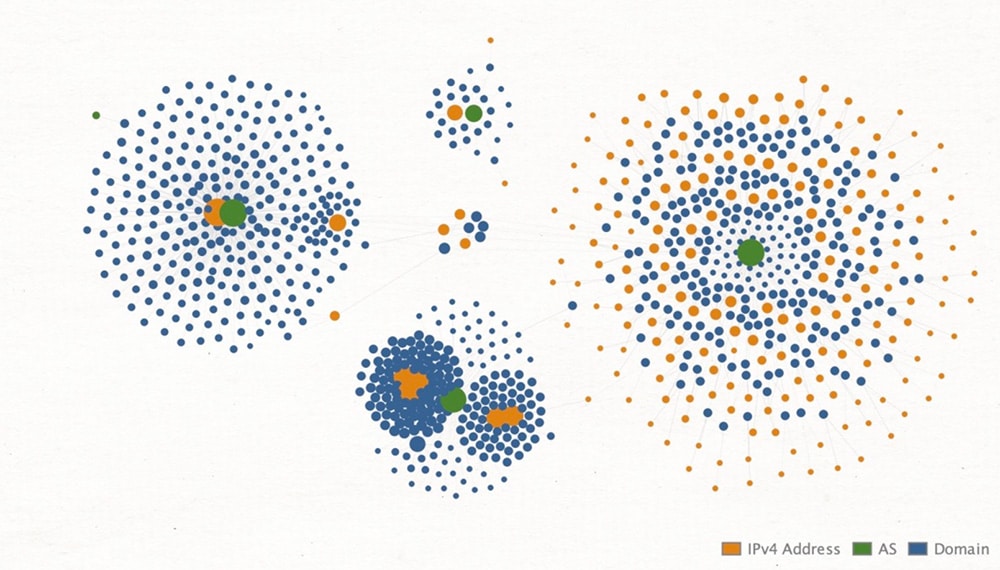

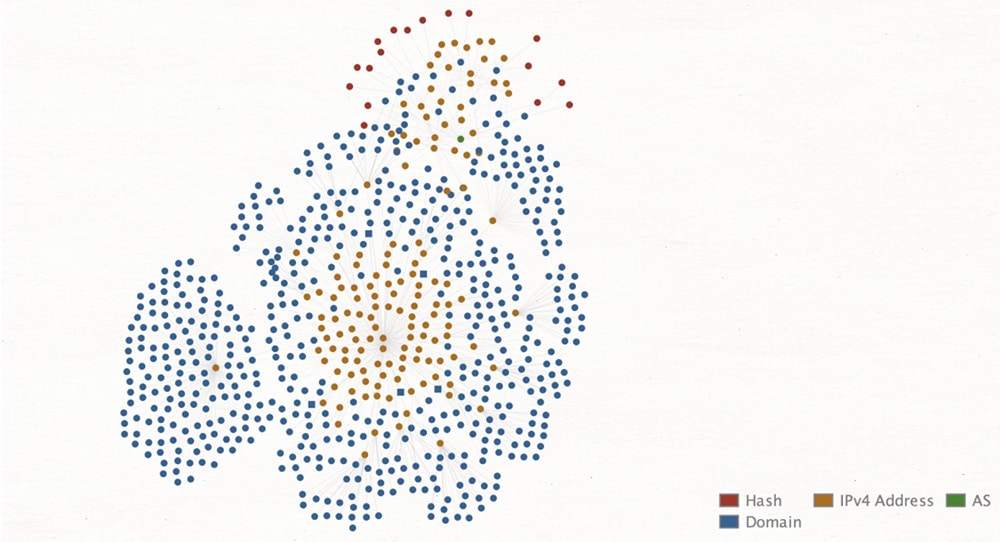

To get a better understanding of the infrastructure related to this operation, we reviewed the passive DNS records of the additional brand domains uncovered through the HTTP requests. While many resolved to Cloudflare IPs from the start, there are a number that didn’t. One IP 165.154.162[.]145 almost exclusively hosts the domains related to Target, and where every domain illustrates the reuse of SSL certificates amongst smaller subsets of the domains in question. Figure 7 shows a Maltego visualization of some of the infrastructure used in the campaign.

An additional pivot off the website title data reveals a plethora of other related domains:

balancegc[.]xyz,httpwwww[.]org,primevideo[.]cyou,secureredeem[.]com,target-6[.]com,targetgrow[.]com,targetpublicizing[.]com,targetmarket[.]cc,targetpublicizing[.]com,teragat[.]com,tgmall118[.]com,tragat[.]net,tragtmall[.]vip,workingtarget[.]cc,wwwhttps[.]cyou,wwws[.]live,wwwhttps[.]cyou,krogerr[.]vip,tarrget[.]shop,tgmall128[.]com,tarrgetmarket[.]shop,tarrgetmraket[.]shop,targetmall[.]cc,targetmarkets888[.]shop,targetmarkets888[.]top,targetmraket[.]cc,targetsol[.]online,tgmall126[.]com,traget[.]shop,emagshop[.]top,targetmarkest[.]shop,targetniokv[.]org,tarrgetmarket[.]cc,targetmraket[.]vip,tarrgetmraket[.]cc,tgmall119[.]com,yjjef[.]com,traget[.]cc,target-001[.]com,targetmarkets[.]top,yfjer[.]com,yuyyj[.]com,tragetmarkte[.]cc,waytotarget[.]com,starbucksgiftscardbalance[.]com,waytotarget[.]vip,limango[.]top,target58[.]com,target58[.]vip,target-8[.]com,targetpiggybank[.]ru,target-002[.]com,target-40[.]com,target-80[.]com,targetbbs[.]com,target-7[.]com,target-15[.]com,target2earn[.]com,tmarketshop[.]vip,targetsmarket[.]club,targetmarket[.]club,targetimprove[.]com,targetmarket[.]vip,targetmarkets[.]shop,targetmarkets[.]vip,omarovdidar[.]kz,tmarketshop[.]cc,digitalsecure[.]shop,logiria[.]com,target-50000[.]com,targetshop[.]online,target-30[.]com,target-60[.]com,target-70[.]com,target-20[.]com,target-1007[.]com,target-55555[.]com,targetmarkets[.]cc,target-19[.]com,target-108[.]com,target-90[.]com,target33[.]com,burazlegabracika[.]com,target-567[.]com,target4digital[.]com[.]br,target-883[.]com,targetksa[.]com,gelaundry[.]shop,zvamp[.]com,targetservices[.]co,targettours[.]inWhile the owner of the IP was listed as UCloud USA with Los Angeles, California as its location, all abuse and contact information list UCloud addresses in Hong Kong, and .cn domains for their contact emails.

To understand more we returned to the HTTP requests again and found this interesting request tied to the domains: [“http://103.106.202.53:10086/income_app/income_update.php”, “http://bigw123.com/income_app/income_update.php”]. It produced an additional IP 103.106.202[.]53, and the domain bigw123[.]com. The domain had resolved to that IP address ever so briefly back in August of 2020, so we decided to enter the IP into VirusTotal to see what other files might have been associated with it. Of the 13 referring files one stood out as being flagged as malicious significantly more than the others. Most recently submitted in mid-March, it tied back to the same domain via the request in the site, and included calls to another domain: freecitph[.]com.

While the domain is inactive as of the time of writing, a few quick OSINT reviews and Google queries shed light on why that is likely the case. There are numerous articles, YouTube videos, and a long list of posts from affected people around the world referencing “freecit” and its connections to crypto and many other related scams including the Ponzi scheme uncovered during the course of this investigation. While data and infrastructure can definitively tie together and expose the malicious schemes of threat actors and the brands they victimize, that same infrastructure empowered countless people to step forward and bravely share their experiences and losses to assist others from facing that same fate. They, too, stepped up to ensure that more bad actors have more bad days.

Cluster Three – Success Sadly Has a Thousand Cousins

Within criminal forums, actors not only trade in stolen data, credit cards, and other items but also trade knowledge and sell countless tutorials on how others can do the same. Actors brazenly market these schemes using a host of social media and messaging platforms. When a fraudulent activity finds success, it’s quickly replicated. This is our third cluster of malicious activity against the Retail sector—a copycat of the second cluster above.

In this investigation, an Iris Detect alert based on the term “target” produced a domain registered in late 2023, targetpk8[.]top. Like others we have seen, it is privacy-protected and uses Cloudflare. A screenshot of the domain in Figure 8 shows that it is intended to fraudulently represent Target Corp. as a retailer.

While the domain, Whois, and IP addresses pose a challenge, we again look to other pivots available when conducting an investigation. In this case, the TLS/SSL certificate shows a number of other domains associated with the same cert. While targetpk7[.]top and the original domain share the same hash, the alternative names listed broaden our search, including targetaa1[.]com, targetdd1[.]com, tgtacting[.]com, and tgtacting[.]vip. A review of these domains shows the same panel for each of them. The naming convention for the series seems to suggest that there could possibly be more registrations like them. A quick advanced search in Iris returns even more domains very similar to what we’ve previously seen:

target7a[.]win,target7b[.]win,target8[.]win,target9[.]win,targetkk88[.]com,targetpp22[.]com,targetpk7[.]top,targetpk8[.]top,targetaa1[.]com,targetdd1[.]comThe .vip domain is also an example of the additional intel that screenshots can provide. Often assets are hosted on different IP addresses than the listed A record, and in this case the screen capture is a wealth of new information in the form of its configuration details, as shown in Figure 9.

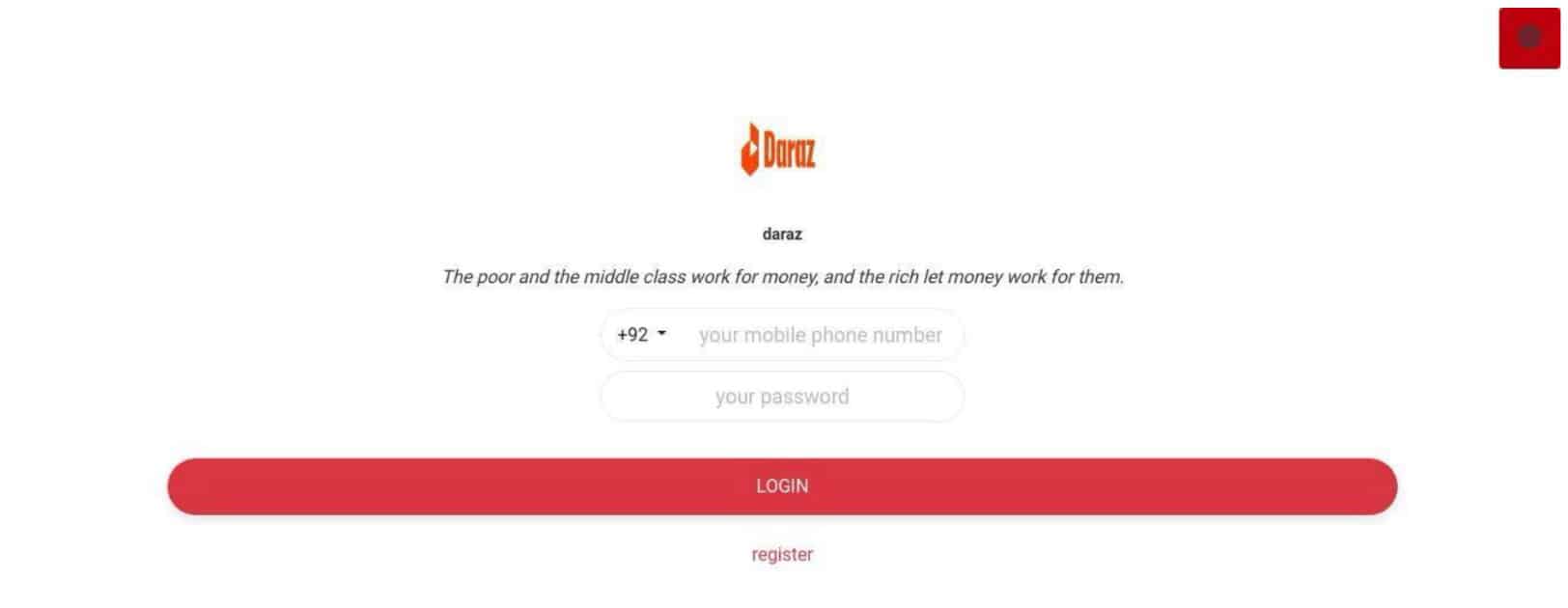

The information collected in the image reveals the connection to targetpk8[.]top and goes on to provide additional information in regard to additional IPs and another domain shopre3[.]vip–a domain submitted to Google Safe Browsing only five months after being registered. Before warming to visitors, shopre3 hosted a familiar panel, this time impacting a large Asian Ecommerce company Daraz, which is owned by Alibaba.

We decided to run a similar process to see if there were domains that might warrant further investigation into this brand, as cybercriminals tend to repeat behaviors in their domain registrations.. Sure enough, domains showing similar naming conventions, TLS/SSL certificate reuse, and website titles appeared and provided more avenues of investigation regarding the actor group and an initial foothold. Additional domains include:

2daraz[.]com,darazpk[.]vip,1daraz[.]com,souq618[.]com,arazpk[.]vip,khobornao[.]online,samalsbp06[.]cc,1daraz[.]com,mercadolibre07[.]com,1mercadolibre[.]com,darazz8[.]top,ayaatus[.]shop,darazaz[.]top,darazz8[.]com,clicktoocart[.]com,dhongtrendy[.]shop,fashionus[.]shop,darazaz[.]com,beautifullifelogisticserviceltd[.]online As this process was repeated, new brands and impacted companies were discovered, including Walmart, Shopify, Amazon, and more. For the sake of brevity, we included a list of additional domains as an appendix to the blog.

The visualization of this cluster is tighter than that of the previous campaign. As shown in Figure 11, the domains all clustered around a set of IP addresses and TLS/SSL hashes, regardless of the brand they were spoofing.

While similar in nature to the previous cluster in its attempts to fraudulently co-opt the brand value and goodwill of large retailers, the process of defrauding victims was more closely aligned with a conventional or traditional Ponzi scheme. No attempt was made to lure people with the false promise of commissions.They instead focused on the speculation in crypto markets and played up the fear of missing out on the next big “overnight” crypto windfall by soliciting victims for modest “investments” at the start.

Like many Ponzi schemes, initial returns were provided to victims in an effort to extract even larger investments from the victim and to induce them to recruit others before pulling the rug out from under them. Because this scam was initially promoted on social media and advertising, it has been overcome to some extent by awareness raised by numerous individuals and other online outlets that focus on customer fraud. As with similar types of schemes, continued diligence and monitoring of threat actor infrastructure helps to blunt the damage of their actions while efforts in pursuing legal remedies for their disruption make their way through the justice system.

Conclusion

As these clusters indicate, the retail sector faces not only the broader threats that businesses more generally face such as ransomware, phishing, and business email compromise (BEC), but unique threats that try to leverage the brand loyalty and the relationship these brands have with their customers. Bad actors may look to use the brand goodwill to sell knockoff goods at steep discounts, defraud victims by stealing banking or other personal information, or even use the brand to convince victims into participating in cryptocurrency-themed Ponzi schemes.

Given the breadth of the infrastructure and domains employed by these actor groups, along with the rate of recidivism they have displayed, it’s imperative for retail brands to maintain regular watch over their activities. The actor groups’ activities go back as far as September of 2020, and so it is clear that they will not likely abandon their campaigns against the retail sector, but will pivot amongst victims and continue to inflict harm on both the brands and their consumers.

Because of this, protecting the broader retail sector against these diverse challenges requires not only the monitoring of actor activity and infrastructure, but the ability to share intelligence with other organizations to help augment and build on the sector’s collective defense. Like other sectors, industry ISACs play a valuable role. The Retail and Hospitality ISAC (RH-ISAC) and organizations like The National Cyber-Forensics and Training Alliance (NCFTA) are a tremendous resource for the retail sector, fostering that collective effort and allowing organizations to benefit from and contribute to shared intelligence and defense. As these examples have shown, threat actors rarely only focus on one organization, and intelligence and data that helps protect one brand can be used to benefit others. Working together helps to ensure that more bad actors have more bad days.