Post-GDPR-Security-Investigations-Part 2

Part II: Non-Registrant Based Connections

Welcome back to my blog series on conducting security investigations in a post-GDPR world. Last week I covered DomainTools Risk Score, and this week I’m excited to dive into non-registrant-based connections.

It’s neither new nor novel, but it is worth remembering in this post-GDPR world that infrastructure isn’t personally identifiable information (PII). This means that researchers can still make connections and attributions based on non-registrant based information using tools like DomainTools Iris.

Aside from Whois information, researchers know there are several other methods by which to tie domains to the same campaign or actor group. One such method is by linking shared infrastructure between domains. Oftentimes, lower level cyber criminals will often host multiple malicious domains on the same IP space or use the same SSL certificate.

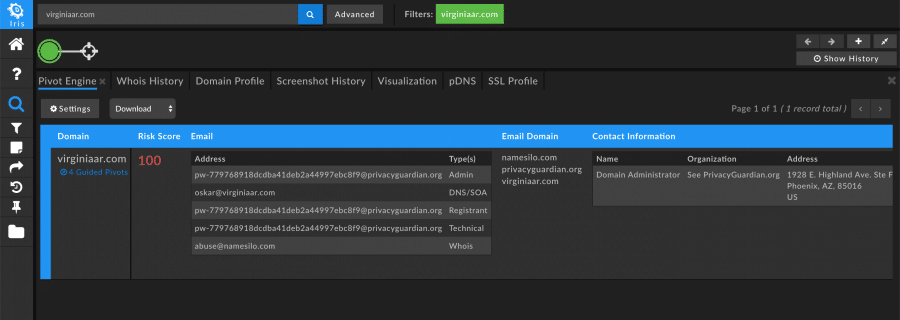

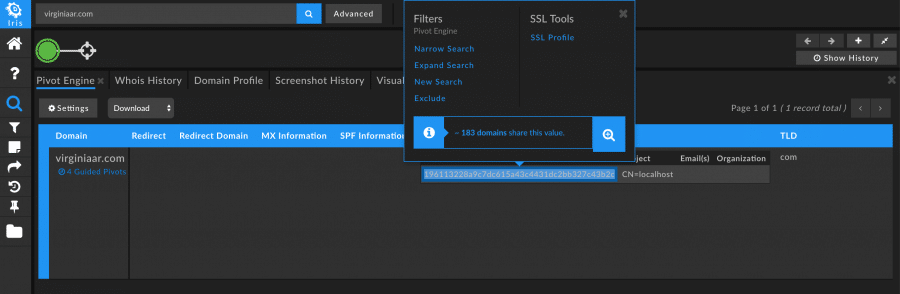

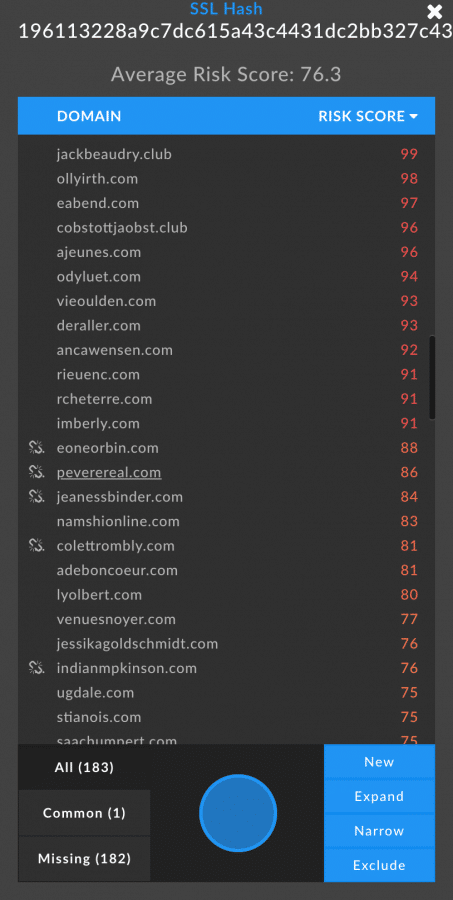

For example, searching on a known APT-related domain and pivoting on the shared SSL certificate hash shows that there are over 180 other domains that are likely also tied to that same APT group.

Viewing those 180 domains shows that many of them are still active and aren’t yet on industry blocklists, and might be worth further investigation or blocking.

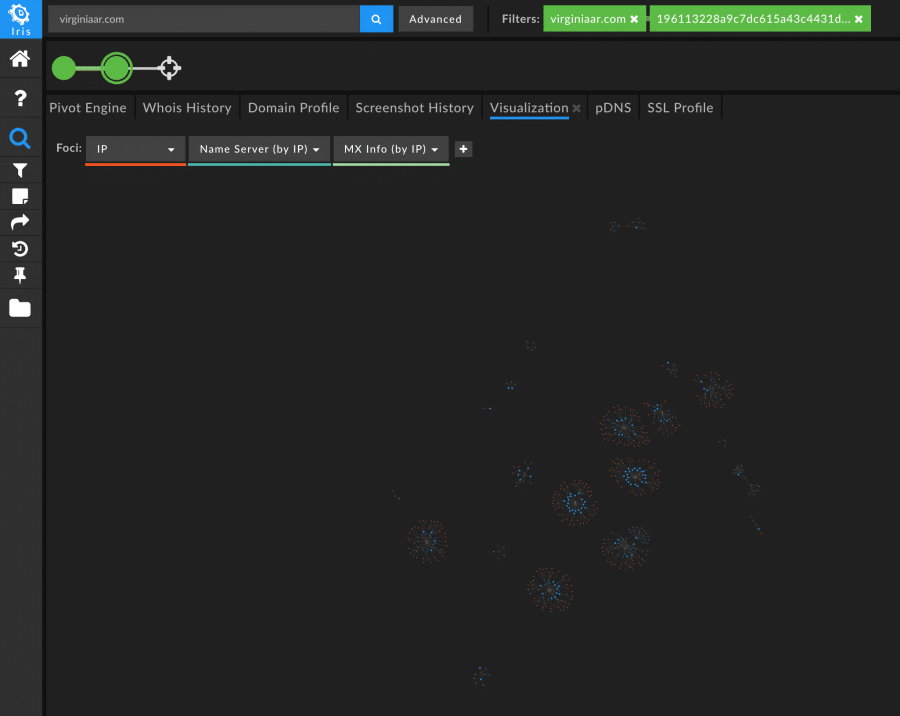

It’s also notable that many of these domains were not linked by any infrastructure other than SSL certificate – as the visualization of IP, mail server IP, and name server IP shows, these domains were otherwise disparate.

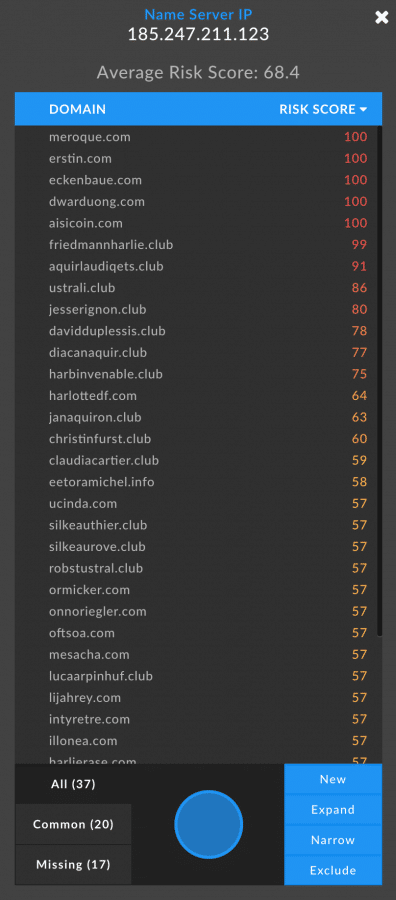

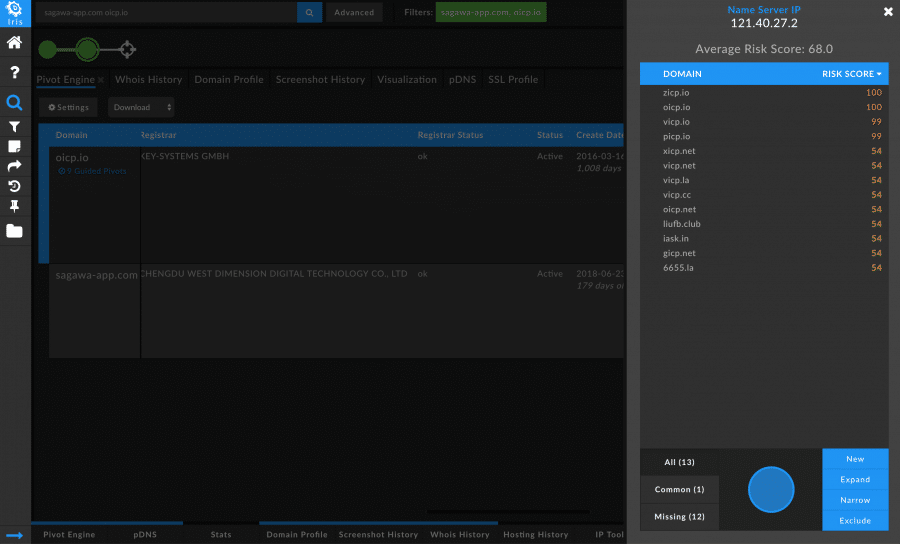

The mostly disparate nature of these domains allows for additional pivoting once they’ve been connected via SSL certificate. Pivoting on the Name Server IP of one of these domains reveals an additional 17 domains that hadn’t been tied to the SSL certificate, which may potentially be linked to the same threat actor or campaign.

Threat actors try to hide their tracks when setting up and conducting malicious campaigns, but frequently leave behind a slew of clues that, when viewed together, form a sort of “digital fingerprint” that can help to identify their actions in the context of other related domains.

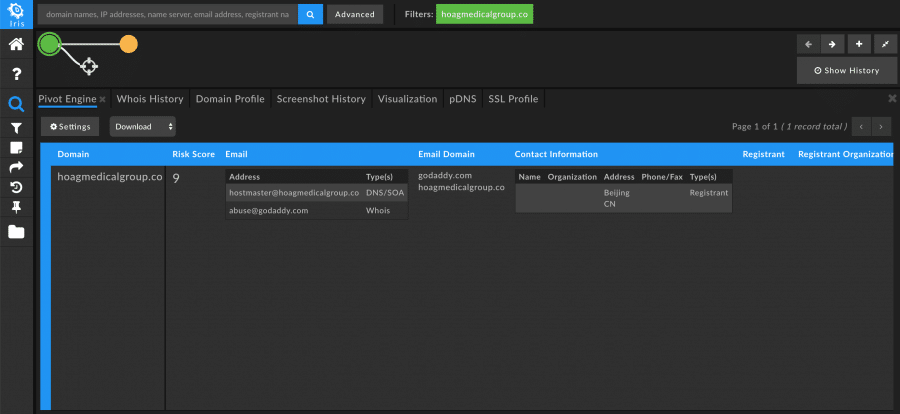

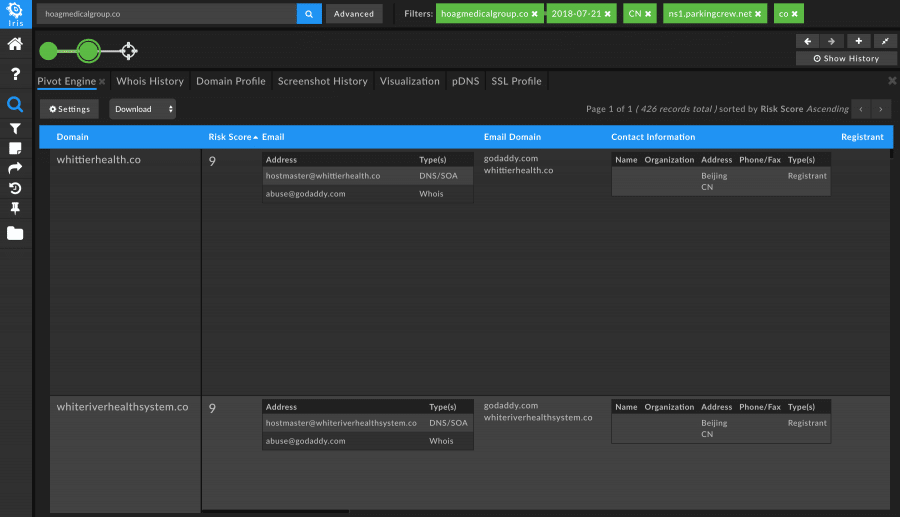

For example, in one particular observed instance, a threat actor registered numerous healthcare-related phishing domains on the same day. However, none of the domains had any obvious linkages to each other and searching for one of the domains in Iris looked to be a dead end.

By expanding and narrowing the search based on specific attributes of the domain – such as create date, country code, name server, and TLD – we were able to identify approximately 400 domains that all appeared to be related to other healthcare institutions. Those attributes made up that particular campaign’s “digital fingerprint,” allowing us to pivot and find more potentially malicious domains related to the same actor and campaign.

As researchers, we’re used to looking for the obvious connections between domains, but sometimes linkages may be more uncommon. In one instance, a particular malicious domain didn’t seem to have any useful pivots to additional maliciousness. It did, however, have a screenshot history.

Reviewing the screenshot revealed that the webpage had instructions for the user to download malicious software onto their phone and included phone screenshots with a different domain in the address bar of the phone.

Searching on that domain reveals multiple other malicious domains tied to the same campaign.

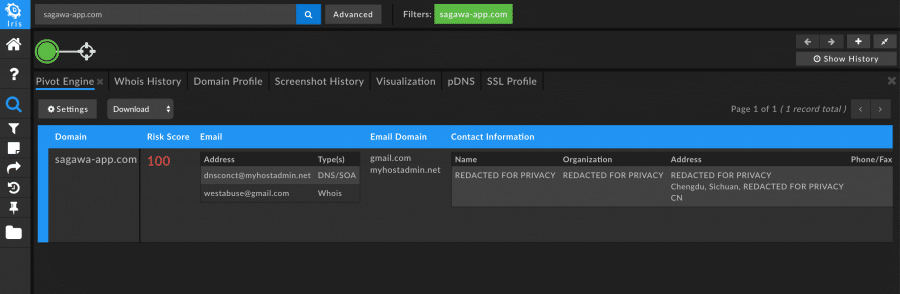

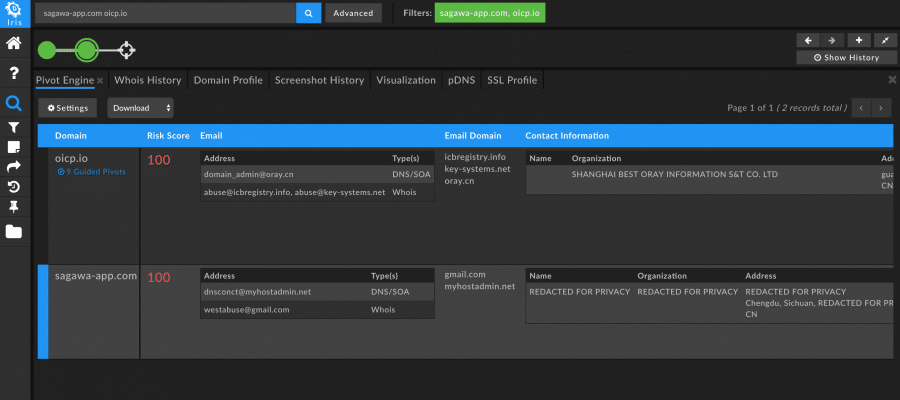

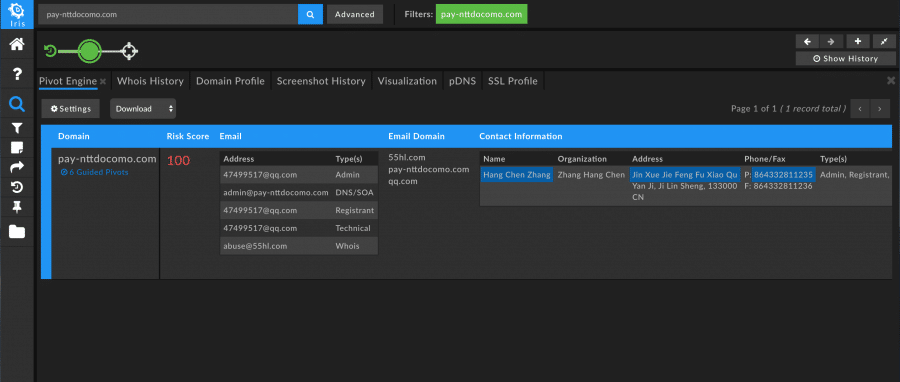

Finally, it is worthy to note that not all registrants have fully adhered to GDPR regulations, especially those that are based elsewhere than the European Union. When conducting an investigation, it may still be beneficial to check Whois information, as beneficial pivots may still be available. Additionally, historical Whois information in Iris may still contain registrant information that had been exposed at some point in time, even if it is private now, and may be useful for finding connections between malicious sites.

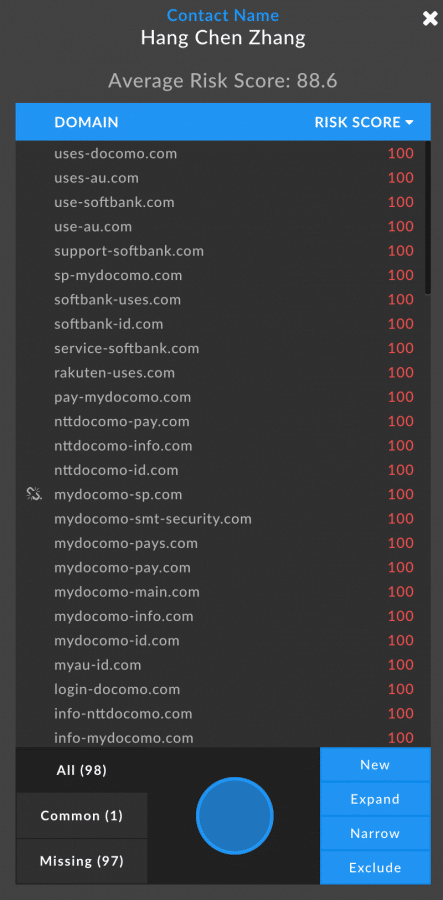

In this example, you can see that just from the the Whois data available, there are potentially beneficial pivots on the registrant Name, Address, and Phone Number. Pivoting on Name shows 97 other malicious and potentially malicious domains.

These examples show that Whois information redacted by GDPR regulation have not truly hindered the intelligence and analysis process. With a little ingenuity, beneficial pivots can still be made to uncover campaigns or threat actors. Join Security Researcher, Ryan Weaver, next Thursday, February 21st, for the final section of this series. This blog will focus on both open source intelligence (OSINT) and other information sharing options.