Extrapolating Adversary Intent Through Infrastructure

Introduction

Adversary cyber operations require communication to victim networks in order to deliver effects on objectives. When performed over public networks, competent adversaries rarely (if ever) communicate directly from their “home” locations but use various proxied infrastructure: servers denoted by IP addresses, or identified via domain names. While there are many instances of adversaries using either pseudo-random or meaningless strings for domains, or eschewing these items altogether and simply communicating directly to an IP address, instances of deliberate adversary name choice can be revealing.

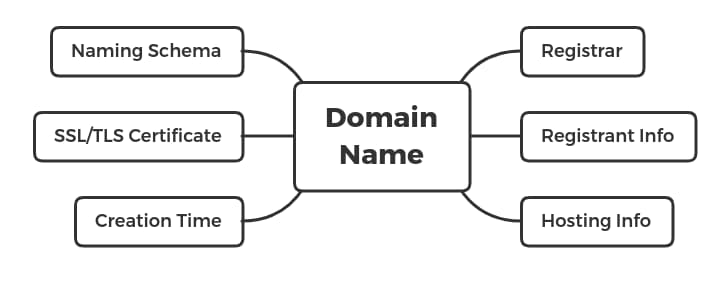

Looking at domain names as composite objects – consisting of multiple components such as the domain registrar or where a domain resolves – allows us to track adversary activity and infrastructure creation through tendencies and patterns. Just as with items such as authoritative name servers or registration information, the very name chosen for a domain has significance, and can identify fundamental adversary behaviors.

Adversaries typically leverage themes in domain creation that can indicate aspects of attacker operations. This could include:

- Blending in with likely “normal” traffic within targeted environments.

- Mirroring services or functions targeted for operations, such as logon portals.

- Matching target characteristics to facilitate interaction or lower suspicion when identified.

By studying adversary naming choices, we can begin identifying various aspects of attacker operations – from how initial access operations may take place through likely victimology based on observations. In the following three examples, we will explore relatively recent campaigns to identify how adversary naming choice and patterns can be used to gain greater understanding of attacker goals and operations.

Sandworm and the 2018 Olympics

Reviewing the recent US Department of Justice (DOJ) indictment against six members of Russian military intelligence (GRU) Unit 74455, commonly referred to as “Sandworm”, shows several infrastructure items related to attacks on the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics:

- Msrole[.]com

- Jeojang[.]ga

The items were used to spoof Microsoft services and the Korean Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs, respectively. As supported in the indictment and other technical analysis, these items were leveraged as themes for infrastructure used to support phishing activity and credential theft.

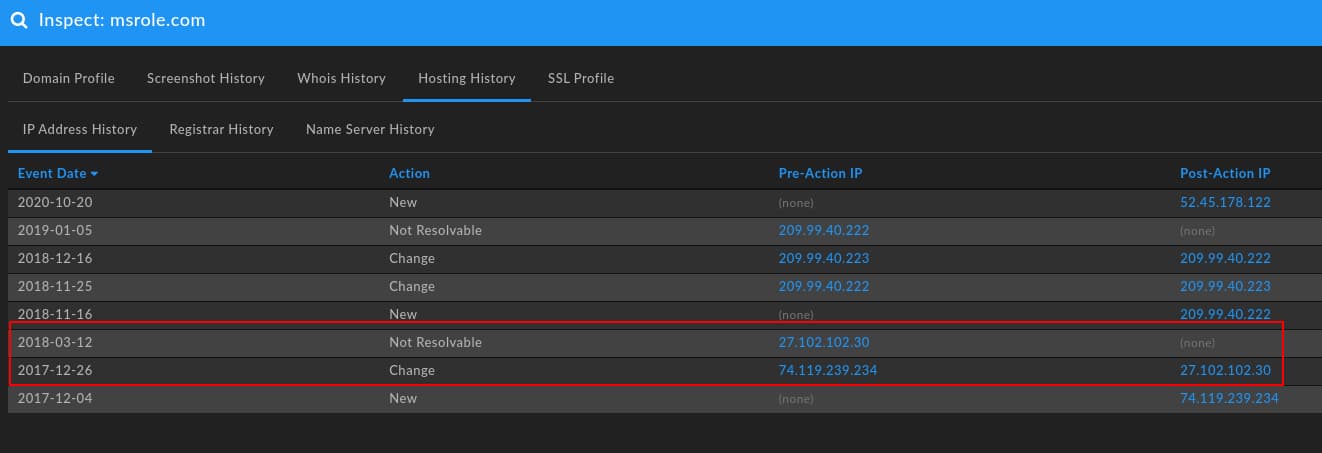

More interesting still, further analysis using DomainTools Iris indicates a wider campaign with additional themes. For example, viewing Passive DNS (pDNS) information for msrole[.]com identifies a series of IP addresses used during the run-up to the Olympics:

Most significant, and highlighted above, is the 27.102.102.30 address. Hosted in The Republic of Korea (ROK, or South Korea), this address hosted msrole[.]com during the period of action prior to the Olympic Destroyer incident during the Pyeongchang opening ceremonies in February 2018. Analyzing this IP address and its history during the time prior to the Olympic Destroyer incident reveals additional details:

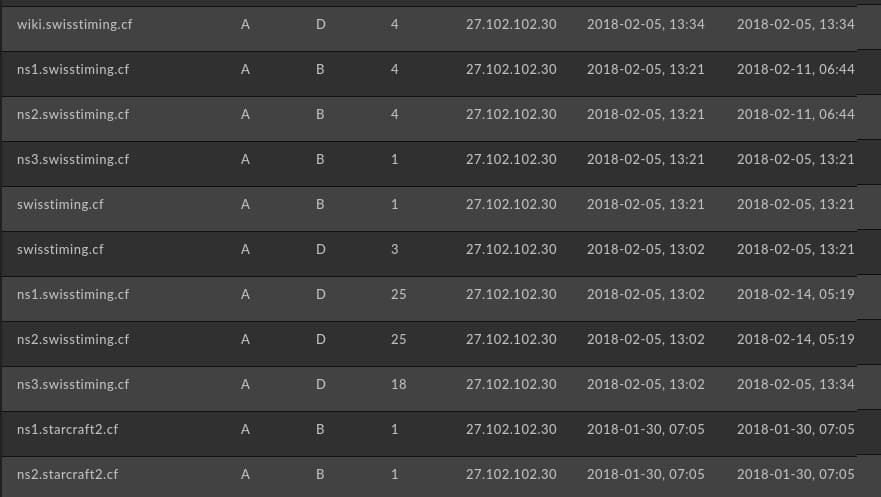

In addition to mapping the movement of msrole[.]com over time, Passive DNS monitoring via DomainTools Iris reveals additional items neither noted in the US DOJ indictment nor previously disclosed as part of the OlympicDestroyer event:

- Culturecommunication[.]ga

- Starcraft2[.]cf

- Swisstiming[.]cf

While “Culture Communication” is somewhat ambiguous, the other items seem appropriately themed for the target event and country: Swiss Timing is the official timekeeper of the Olympic Games (including the 2018 Winter Games) through 2032; while StarCraft (both the original and its sequel) remains one of the most popular games (and esport events) in ROK.

Irrespective of other observables (some of which are now unavailable over two years after the events in question), the names used by the GRU operators in creating infrastructure reveal degrees of intentionality. As already stated (without details) in the DOJ indictment, actions included operations linked to the official Olympics timekeeper organization – unearthing the specific domain confirms this observation. But the StarCraft spoof indicates potentially wider targeting of ROK persons, leveraging the popularity of the game to create a mechanism (whose precise functionality is indeterminate now) to further operations against the ROK-hosted games.

While we have unearthed additional indicators of compromise (IOCs), more importantly through analysis of infrastructure we identified a pattern in domain creation centered on a combination of technology (Microsoft spoofing), culture (the StarCraft item), and event (the 2018 Olympics).

Sandworm IOCs

Msrole[.]com Jeonjang[.]ga Culturecommunication[.]ga Templates-library[.]ml Starcraft2[.]cf appmicrosoft[.]net Swisstiming[.]cf 27.102.102[.]30 141.8.224[.]221 200.122.181[.]63 107.167.92[.]196 195.20.51[.]47

Energetic Bear and Airports

In October 2020, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) released a joint report on malicious actor targeting of local government and related critical infrastructure entities in the United States (US). Linked to an entity assessed by US government sources to be Russian state sponsored and called variously Energetic Bear, Dragonfly, Crouching Yeti, or ALLANITE, the operations focused on spoofing legitimate websites as a mechanism for gathering credentials to enable follow-on intrusions.

First emerging in Spring 2020 with a compromise at San Francisco International Airport, this specific campaign appears to have expanded significantly to include a number of other locations and regions within the United States – often focused on airports.

Of interest in the Energetic Bear campaign though is the shift from credential theft via strategic website compromise – seen in the code snippet found in the SFO website in ESET’s Tweet – to more direct credential phishing. As listed in CISA Alert AA20-269A, the attacker shifted operations from indirect credential capture to more direct forms through website spoofing.

This behavior is reflected in domains observed in the campaign:

- email.microsoftonline[.]services

- columbusairports.microsoftonline[.]host

Additionally, CISA notes a pattern of infrastructure using the following domain name pattern associated with Microsoft Azure cloud services:

[City Name].westus2.cloudapp.azure[.]com

Reviewing pDNS data via DomainTools Iris shows that these items all link back to similar infrastructure during their time of weaponization:

Primary domain themes – spoofing Microsoft – reflect the shift in adversary behavior. When paired with exploit chaining as documented in a related CISA alert, overall the collection of observed behaviors including domain themes demonstrate a significant overall change in Energetic Bear tactics, techniques, and procedures. Identifying such developments as they emerge allows defenders to appropriately adapt security measures and analysis of potential incidents.

Energetic Bear IOCs

Microsoftonline[.]host Microsoftonline[.]services 213.74.101[.]65 138.201.186[.]43 213.74.139[.]196 5.45.119[.]124 212.252.30[.]170 193.37.212[.]43 5.196.167[.]184 146.0.77[.]60 37.139.7[.]16 51.159.28[.]101 149.56.20[.]55 108.177.235[.]92 91.227.68[.]97

Kimsuky Infrastructure and Themes

On 27 October 2020, CISA released an extensive report covering activity associated with the Kimsuky actor. Linked to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea), Kimsuky is responsible for multiple campaigns against ROK critical infrastructure entities, Korean peninsula nuclear negotiation entities, and various targets in ROK, Japan, and the United States.

In addition to coverage of Kimsuky intrusion techniques and behaviors, the CISA report contains nearly one hundred network indicators in the form of domains and subdomains. Reviewing the naming conventions used identifies three broad themes:

First, spoofing popular services, especially in ROK, for infrastructure creation. For example, Kimsuky targets ROK web portal and search engine Naver in multiple instances, such as:

Help-navers[.]com naver.com[.]se Helpnaver[.]com naver.hol[.]es naver.co[.]in naver.koreagov[.]com naver.com[.]cm naver.onegov[.]com naver.com[.]de naver.unibok[.]kr naver.com[.]ec naver[.]cx naver.com[.]mx naver[.]pw naver.com[.]pl naverdns[.]co

Similar activity surrounds Korean webportal Daum:

daum.net[.]pl login.daum.kcrct[.]ml Daurn.pe[.]hu login.daum.net-accounts[.]info daurn[.]org login.daum.unikortv[.]com

Service spoofing such as the above can be used to either mimic pages for exploitation or credential harvesting, or as a means to hide command and control (C2) communications. However, geographic specificity in these particular cases indicate the domains in question are almost certainly limited in application to Korean-language audiences. As such, while these items are interesting in learning about Kimsuky activity, they are likely less significant from a defensive action standpoint for non-Korean entities.

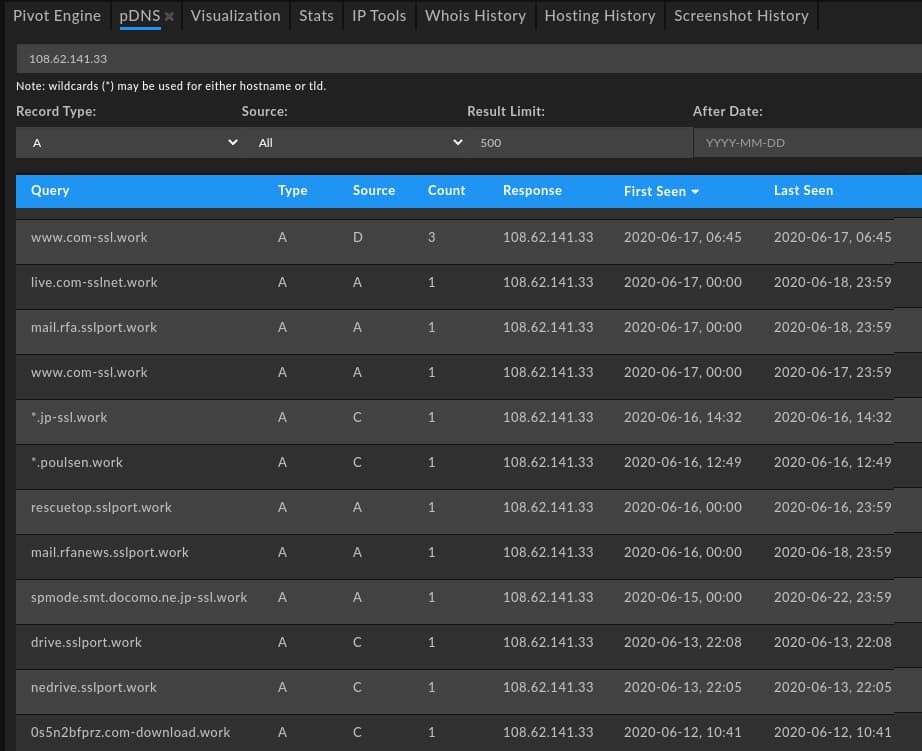

Second, and as observed in some of the domains above, Kimsuky features a pattern of persistent service spoofing especially centered around webmail or cloud storage logon pages. This is expressed through a pattern of subdomain creation reflected across multiple domains, all hosted on the same infrastructure during use. As shown in DomainTools Iris pDNS results, a familiar pattern emerges with mail-themed subdomains linked to generic, IT-themed primary domains:

Reviewing items active in Kimsuky-related operations shows a persistent pattern. First, a “generic” technical domain is used as a root item (e.g., “com-ssl[.]work” or “com-vps[.]work”), followed by a common sequence of webmail or related subdomains:

- Mail2

- Drive

- Onedrive

- Login

The thematic basis behind these items (“e.g., “onedrive.sslport[.]work”) implies intentionality as a mechanism for serving a spoofed logon page (in this specific example, for the Microsoft OneDrive service) for credential gathering.

Third, and observed in the subdomains examined above, we can also glimpse potential specific targets of Kimsuky campaigns as reflected in naming patterns and conventions. For example, the following items appear to indicate targeted institutions:

- Intranet.ohchr.account-protect[.]work

- Smt.docomo.ne.jp-ssl[.]work

- Rfanews.sslport[.]work

- mail.rfa.sslport[.]work

The above items appear to mimic the legitimate domain naming patterns of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (ohchr.org), Japanese telecommunication company NTT Docomo (nttdocomo.co.jp), and Radio Free Asia (rfa.org). Along with domains which reference subjects such as Korean unification, these items allow us to expand our view of Kimsuky activities to include “soft” targets in consumer communications, human rights causes, and similar entities beyond classic espionage goals.

Analyzing Kimsuky infrastructure activity allows defenders to glimpse not only attacker methodologies but also potential targets – in terms of both targeted services and targeted organizations. With this relatively minimal amount of information, defenders can better understand Kimsuky motivations and appropriately vector resources for defensive and monitoring purposes.

Kimsuky IOCs

account.daum.unikftc[.]kr hogy.desk-top[.]work account.daurn.pe[.]hu intemet[.]work amberalexander.ghtdev[.]com intranet.ohchr.account-protect[.]work beyondparallel.sslport[.]work jonga[.]ml Bigfile.pe[.]hu jp-ssl[.]work bignaver[.]com kooo[.]gq Cdaum.pe[.]hu loadmanager07[.]com cloudmail[.]cloud login.daum.kcrct[.]ml cloudnaver[.]com login.daum.net-accounts[.]info coinone.co[.]in login.daum.unikortv[.]com com-download[.]work login.outlook.kcrct[.]ml com-option[.]work mail.unifsc[[.]com com-ssl[.]work mailsnaver[.]com com-sslnet[.]work member-authorize[.]com com-vps[.]work myaccount.nkaac[.]net comment.poulsen[.]work myaccounts.gmail.kr-infos[.]com cooper[.]center myetherwallet.co[.]in csnaver[.]com myetherwallet.com[.]mx daum.net[.]pl naver.co[.]in Daurn.pe[.]hu naver.com[.]cm daurn[.]org naver.com[.]de dept-dr.lab.hol[.]es naver.com[.]ec desk-top[.]work naver.com[.]mx downloadman06[.]com naver.com[.]pl dubai-1[.]com naver.com[.]se eastsea.or[.]kr naver.hol[.]es gloole[.]net naver.koreagov[.]com help-navers[.]com naver.onegov[.]com help.unikoreas[.]kr naver.unibok[.]kr helpnaver[.]com naver[.]cx naver[.]pw securetymail[.]com naverdns[.]co servicenidnaver[.]com net.tm[.]ro smtper[.]cz nid.naver.com[.]se smtper[.]org nid.naver.corper[.]be sslport[.]work nid.naver.unibok[.]kr sslserver[.]work nidlogin.naver.corper[.]be ssltop[.]work nidnaver[.]email sts.desk-top[.]work nidnaver[.]net taplist[.]work ns.onekorea[.]me tiosuaking[.]com org-vip[.]work top.naver.onekda[.]com preview.manage.org-view[.]work usernaver[.]com pro-navor[.]com view-hanmail[.]net read-hanmail[.]net view-naver[.]com read-naver[.]com vilene.desk-top[.]work read.tongilmoney[.]com vpstop[.]work resetprofile[.]com webmain[.]work resultview[.]com webuserinfo[.]com riaver[.]site ww-naver[.]com sankei.sslport[.]work 108.62.141[.]33 203.249.64[.]219 146.112.61[.]107 211.38.228[.]101 150.95.219[.]213 27.102.107[.]221 162.244.253[.]107 27.102.127[.]46 173.234.155[.]126 27.255.77[.]110 192.185.94[.]206 44.227.65[.]245 192.203.145[.]170

Conclusion

Examining the three separate campaigns above, as defenders we are able to infer adversary intentionality and purpose based on little more than analysis of domain naming schema. When combined with further research, such as additional pivots in DomainTools Iris into SSL/TLS certificates, hosting infrastructure, and registration patterns, defenders can leverage this knowledge to gain even greater understanding of attacker operations.

Yet even without significant additional information, minimal pivoting unearths items of significance:

- Sandworm activity targeting multiple areas of South Korean society and the 2018 Olympics in the run-up to Olympic Destroyer.

- Energetic Bear shifting operations from passive credential collection via strategic website compromise to more active credential phishing through spoofed domains.

- Kimsuky operations targeting prominent commercial and non-government organizations beyond traditional espionage targets via likely credential capture resources.

Armed with this information, defenders can make nuanced, informed decisions about adversary development. With such understanding in hand, defenders can appropriately adjust security controls and visibility to match observed behaviors. While more robust mechanisms for research and analysis exist to allow us to dig even deeper, simple recognition of naming patterns and their implications can prove quite powerful in furthering security operations.