Domain Blooms: Identifying Domain Name Themes Targeted By Threat Actors

Summary

Threat actors have no qualms with taking advantage of any crisis in the world they can capitalize on. Whether it’s a hurricane, political unrest, or even a pandemic, threat actors will try to blend into the world’s online response and create fraudulent infrastructure in order to make money, steal PII, or even induce civil unrest. Mapping out the online response to different world events is the first step in being able to identify what themes threat actors are targeting at any given time.

DomainTools conducted research into what we call Domain Blooms is our attempt to identify new and trending themes in domain names being registered, and highlighting which ones threat actors are potentially targeting for their malicious campaigns.

For an in depth analysis of some of the more notable domain blooms that occurred during 2020 take a look at the The DomainTools Report: Spring 2021 Edition.

Background

Back in February 2020, when COVID-19 was rapidly gaining international awareness, threat actors were actively taking advantage of the situation and registering hundreds of malicious COVID-19 related domains per day. The DomainTools Security Research Team was scanning newly registered COVID-19 related domains daily and ran across coronavirusapp[.]site, which claimed to have a real-time Coronavirus tracker app available for download.

The security researchers pulled down the Android app, went to town ripping it apart and discovered it was really a ransomware app that would lock the victim’s phone and demand $100 in Bitcoin to regain access to the device.

This was a valuable find and it raised a couple questions. First, security researchers need to have a good gut feeling for what words to lookup each day when scanning newly registered domains. But what about other related words that threat actors are capitalizing on that get missed? Second, the rapid increase in COVID-19 related domains was a visible trend, but what about the next one that isn’t as obvious? How can we identify the next trend in domain names that threat actors are targeting and which words they are using?

Telling the Story of COVID-19 Through Domain Registrations

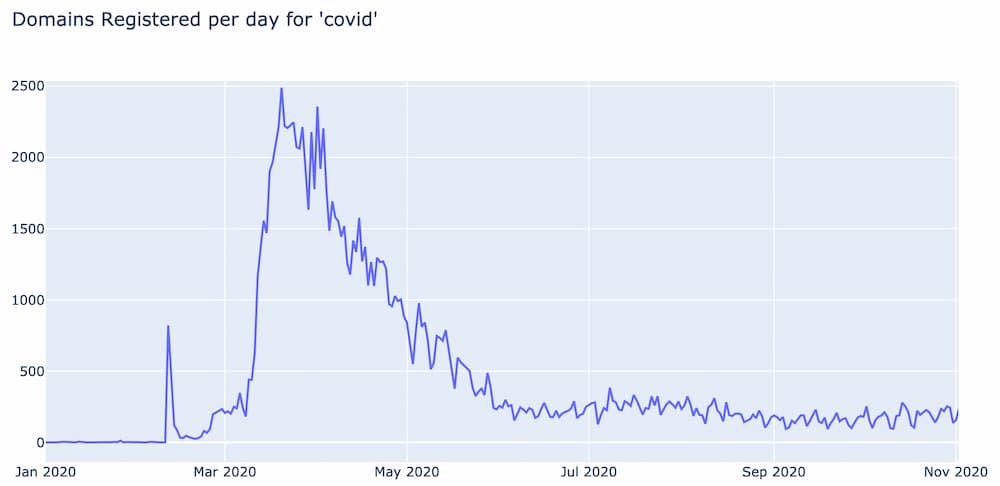

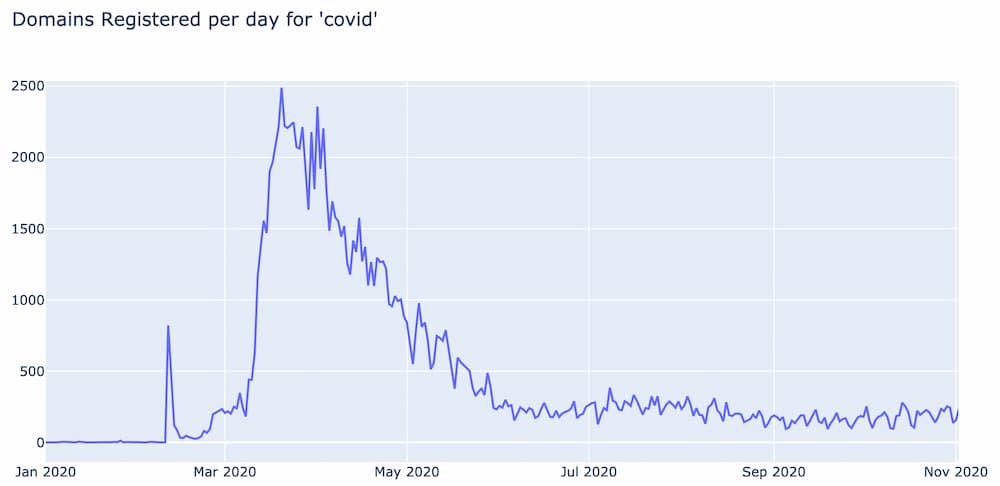

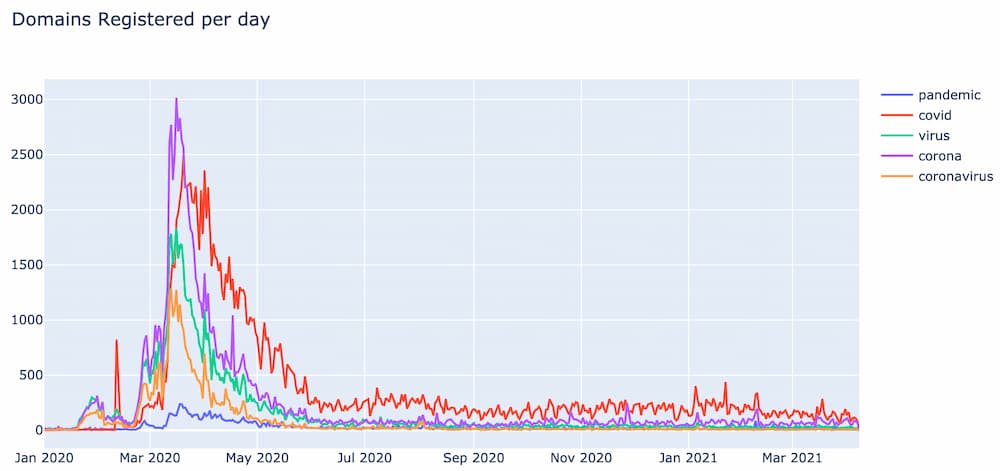

When DomainTools first started analyzing COVID-19 related domains, one of the early visualizations used was a histogram of the number of domains registered per day for a specific word. Below is the histogram for the word “covid” for 2020 and it tells us several things.

First, prior to February, 2020 the word “covid” was almost never used in domain name registrations. Then on February 11th, over 800 domains were suddenly registered using the word “covid”. This date corresponds to the day after the World Health Organization (WHO) officially named the disease “COVID-19”.

By February 14th, the number of daily “covid” domains dropped down to a couple dozen per day and remained steady for about a week and a half. Then in late February, the number of domains started to increase again and continued to do so until March 12th, at which point they skyrocketed to an unprecedented 2500 domains registered in a single day. This turns out to be the day after the WHO officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

From mid March to early April the number of “covid” domain registrations exceeded 2,000 daily, and then started to gradually drop, eventually settling at a new baseline of around 200 domains per day where it has held steady ever since.

You might be asking yourself “what is the purpose or intent behind these domains?” Some were official COVID-19 informational domains created by different municipalities, health and nonprofit organizations. Some were misinformation and disinformation domains; sketchy but not a threat from a cyber security perspective. Many were the result of domain name speculation that inevitably seems to follow any crisis or news event. But a large number of these domains were created by threat actors for fraud, phishing, and Personally Identifiable Information (PII) collection purposes.

Applying the Micro to the Macro

One of the primary goals of data science in cybersecurity is to analyze the tactics and techniques that security researchers use every day and try to apply them algorithmically to the data at scale.

Following this modus operandi, instead of trying to guess which words to monitor each day to identify new themes in domain name registrations, we chose to monitor all words every day and analyze each word’s frequency distribution over time to identify outliers from their baseline frequency.

But word frequency isn’t the only useful metric to measure. Understanding how unique a word or term is provides a lot of valuable insight. Before February 11th, 2020 the word “covid” was used in domain names only a couple hundred times; mostly as part of a larger word or as a by-product of the combination of two words. Identifying new unique trending words could also be useful when trying to find trends threat actors are taking advantage of.

Measuring Word Importance in Domains

One of the most common statistical measures that covers both word frequency and uniqueness is TF-IDF. TF-IDF stands for Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency and is a measure of how important a word is to a single document, relative to a known set of documents (also known as a corpus).

More formally, Term Frequency (TF) is the count of a word within a single document. Words that are used more often within a document can have more influence on the semantic meaning of the document. Words that are used only once or twice within a document have less influence on the semantic meaning, especially for longer documents.

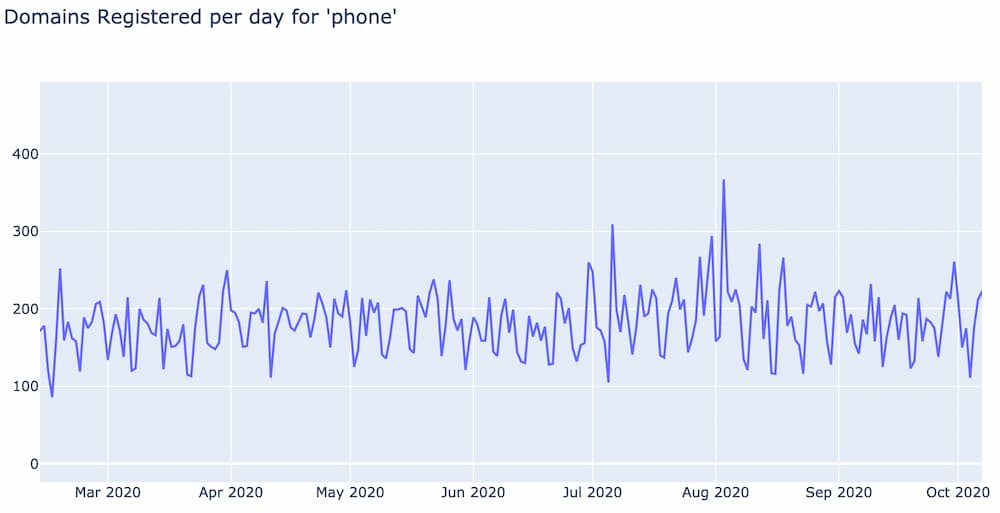

Inverse Document Frequency (IDF) is a measure of how much information a word provides relative to the entire corpus of documents, and is calculated using the function:

where N is the total number of documents in the corpus, and DFt is the number of documents containing the word t. The higher the number of documents the word appears within the corpus the lower its IDF score, and conversely the fewer documents the word appears in the higher its IDF score.

To put this all together with an example, let’s take Wikipedia.com. This year, Wikipedia passed 6 million english articles; so the Wikipedia corpus is 6,000,000 documents. It’s safe to assume the word “the” appears in every single document within the corpus. So “the” has an IDF score of: log(6,000,000 / 6,000,000 +1) = 0.30.

Let’s compare the IDF score for “the” to the word “dragon”. “Dragon” appears in 3,340 Wikipedia documents, giving it an IDF score of: log(6,000,000 / (3,340 + 1)) = 3.25.

(Note: 1 is added to the denominator to protect against divide by zero errors in case a word doesn’t appear in any document)

When looking at the Wikipedia article for Dungeons & Dragons, the TF-IDF score for “the” and “dragon” can be calculated to show how important these two words are to the article.

The word “the” has a Term Frequency of 1,705 in the article, giving it a TF-DIF score of:

1,705 * 0.30 = 511.5.

The word “dragon” has a Term Frequency of 1,092 in the article, giving it a TF-IDF score of:

1,092 * 3.25 = 3549

So when comparing these two words within the context of the Dungeons & Dragons article, it can be seen that “dragon” is much more important than to the semantic context of the article than the word “the.”

Defining a Document

This same statistical measure for measuring the importance of a word can be applied to domain names, but first we have to define what a document is within the context of domain registrations.

Since the goal is to identify word trends in domain name registrations over time, one approach is to consider all the domains registered in a single day as a single document, and all the individual words that make up these domains as the set of words that make up the document.

For example, take June 1, 2020; on this day 285,835 domains were registered. Once each domain is split apart into its component (English) words, there are a total of 2,595,402 words used to register domains for that day. This would represent a single document within our corpus.

Note: to give a sense on how much repetition there is in words used to register domains each day, even though there were almost 2.6 million total words used to generate domains on June 1, 2020, there were only 213,244 unique words.

Defining a Corpus

A corpus is defined as all the writings or works of a particular kind or on a particular subject. In the Wikipedia.com example, the corpus was all the English articles in Wikipedia. The IDF score tells us how important a word is within the entire corpus of all documents. So when calculating IDF scores for words used to register domain names it’s important to define the scope of the corpus in order to calculate meaningful Inverse Document Frequency (IDF) scores.

The corpus could be defined as every day since some arbitrary date, but that has some issues. Since the goal is to identify new and trending words that threat actors might be targeting, going too far back in time has the potential of down weighting IDF scores for words that are currently trending, but have also trended in the past.

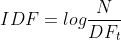

Take the word “Christmas” for example. If the beginning of the corpus is set as July 1st, 2018, the number of times “Christmas” is used per day looks like the following.

Notice there is a predictable annual increase in the number of domains per day starting in early September and lasting until the end of December.

If on October 1, 2020 one was looking for uniquely trending words, the IDF score for Christmas would have included counts from the trending peaks back in 2018 and 2019. This can potentially lower Christmas’s IDF score to the point where it no longer identifies Christmas as a newly trending word.

To get around this problem, the IDF score is calculated based on a sliding 180 day historic window. So, for each day, for each word, the IDF calculation uses the prior 180 days as it’s corpus of documents to calculate that word’s IDF score. For example, on October 1, 2020, Christmas’s IDF score is calculated based on the number of days it was used between April 4, 2020 and October 1 2020.

This sliding 180 day historic window enables the TF-IDF score to identify words that are uniquely trending now, regardless of how the word trended during prior years.

Identifying Domain Name Words

The next challenge is breaking apart domain names into their component words. There are multiple approaches to handling this problem, but the one that was most successful was to compare newly registered domain names each day against a dictionary of all known words. If a known word was found within a domain name, it was output into a list of all words comprising that domain name.

Unfortunately not every trending word can be found in even the most popular dictionaries. For example, the word “covid” wasn’t added to most online dictionaries until after February 11th, 2020. So to try and capture the most representative set of English words, the following sources of were parsed and merged into a gold standard dictionary:

- Three open source online dictionaries

- Google n-gram dataset

- Urban Dictionary

- Parsed words from Wikipedia’s current events page (updated daily)

The Wikipedia current events page has been a valuable source of new important words or phrases that were not represented in the other word sources.

Another challenge in identifying words in domain names is to algorithmically understand which words the registrant was targeting when they registered the domain name. Take the fictitious domain sharepoint-chasebank-login[.]com.

The list of all possible English words from this domain are:

- share

- hare

- point

- repoint

- sharepoint

- chase

- bank

- log

- login

A threat analyst would immediately focus on the words “sharepoint” and “login” and not split them into smaller words, but algorithmically it’s much harder to interpret what the registrant intended.

There are all sorts of different heuristics and probabilistic approaches to addressing this, but each have the drawback of potentially missing important words. Instead the naive approach of just using all words found in the domain name ends up working quite well.

From this data TF-IDF model it is now possible to investigate how words are used in domain name registrations over time.

Domain Blooms and Spikes

Whenever noteworthy events happen, inevitably people will use words and themes to register domains related to the event. If enough domains related to this theme are registered over a short period of time, these domains can be described in one of two different ways; domain spikes and domain blooms.

Baseline Word Frequency

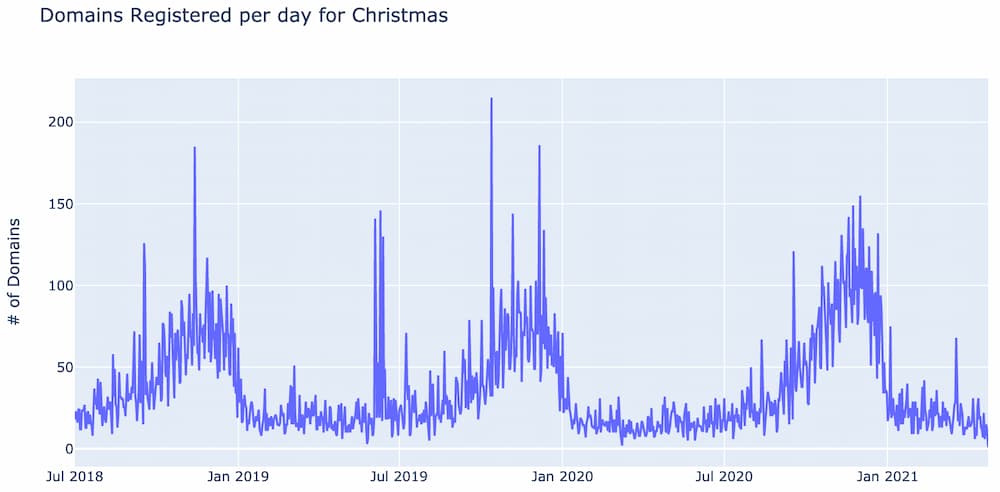

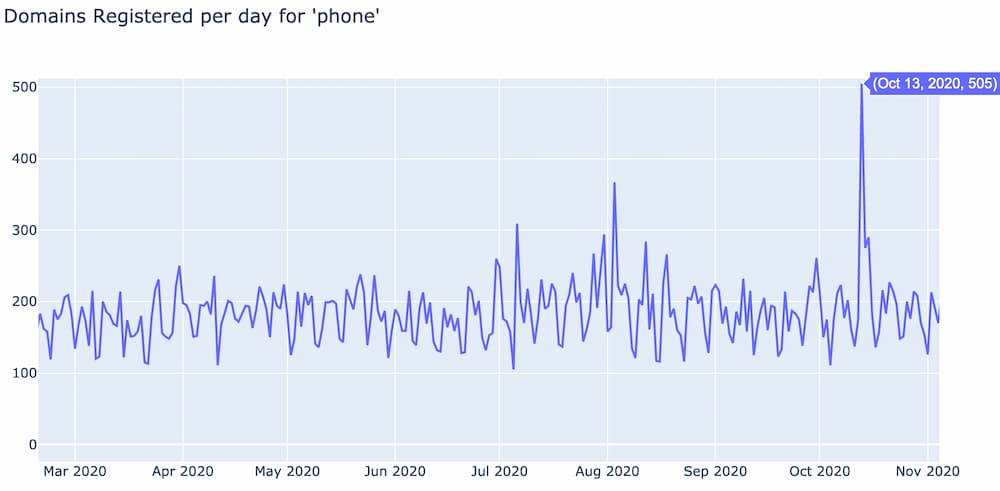

Most words have a baseline frequency in which they are used in domain registrations per day. This baseline is generally fairly stable over time, and is often characterized by a 7 day cycle as people register fewer domains on the weekends. For example, below is the term frequency per day of the word “phone”.

Notice how generally the word “phone” shows up in approximately 180 domains per day, fairly consistent over time. This pattern is what we call a word’s baseline frequency.

Domain Spikes

What becomes interesting is when outliers are identified from this baseline. For example, the below graph shows the term frequency for “phone” extended out to November. Notice how on October 13 there was an increase in domains registered for “phone” that is 300 domains greater than the baseline. We call domain registration events like this spikes.

A domain spike is a sharp increase in the number of domains registered per day for a specific word relative to its baseline. Spikes happen usually the day after some event occurred related to that word and often last only one to two days. The above spike corresponds to the October 13, 2020 release of Apple’s iPhone 12.

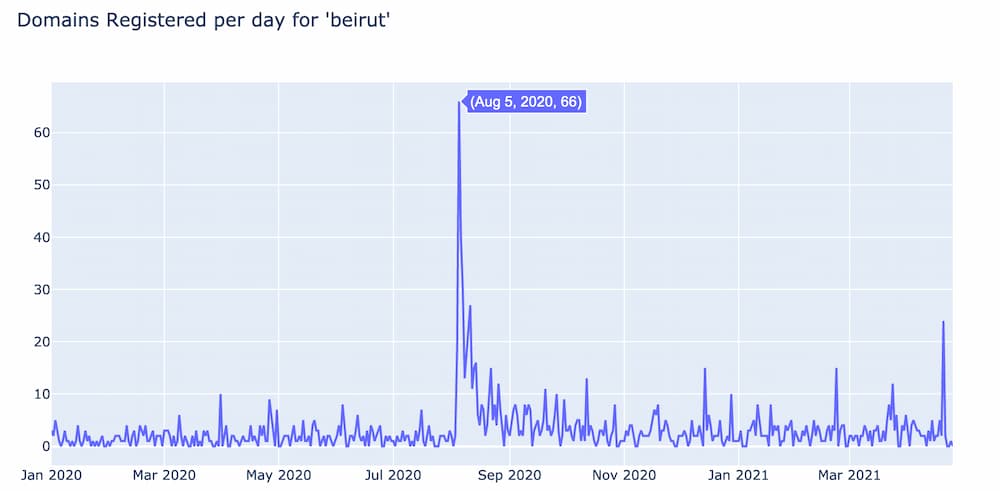

Another example of a news related spike is the one below for the word “beirut” which corresponds with the explosion in Beirut of a fertilizer storage facility that killed more than 200 people on August 4th, 2020.

Notice that the Beirut spike didn’t appear until the day after the news event, while the phone spike was on the same day as the iPhone 12 release. These two domain spikes represent two different behaviors.

The iPhone 12 spike occurred on the same day as Apple’s product event and digging into the DomainTools database it turns out that a large number of them were actually registered by Apple Inc; most likely trying to take the domain names off the market so others can’t profit off them or use them in ways that violate Apple’s trademarks.

The Beirut spike is in response to a tragic incident and looking at the domain names in this spike a lot of them are themed around helping the people of Beirut.

helpbeirutlb[.]com help4beirut[.]com hope4beirut[.]com helpforbeirut[.]com hopeforbeirut[.]com donateforbeirut[.]com donate-beirut[.]com donatebeirut[.]com givetobeirut[.]com fundbeirut[.]com aidbeirut[.]com beirutfund[.]com

Unfortunately, when looking at the domains today almost all of them are just parked domains, most likely registered by domain speculators trying to snap up domains they felt some relief organization might want to purchase.

DGA Domain Spikes

A special category of domain spikes identified are those created by dictionary based domain generating algorithms (DGAs). DGAs are algorithms that automatically generate and sometimes register domain names used by malware and botnets for communication coordination. DGAs traditionally generated domain names with random alpha-numeric sequences. These were fairly easy to spot since their character distributions were so different than legitimate domain names.

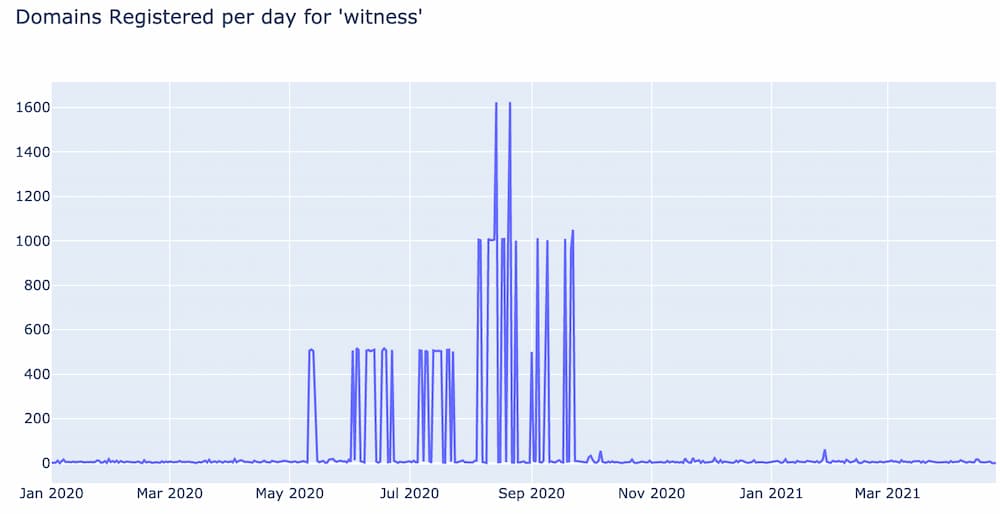

Dictionary based DGAs on the other hand try to get around this type of detection by randomly combining dictionary words to create domain names that closely mirror character distributions of legitimate domains. But these are also fairly easy to spot when you know what to look for. For example, look at the number of domains registered per day using the word “witness”.

There are several indicators that point to the fact that almost almost every spike was generated by a dictionary DGA. First, take a look at the baseline before May and after October; there is a consistent baseline of about 10 domains per day with the word “witness”. Next, if you look at the peak of each spike, each one is some multiple of 500 domains. Such exact patterns like this do not happen in the wild, and clearly point to some script that automatically generates and registers domain names in batches of 500.

Another way to identify dictionary based DGAs is to visually scan the domain names that make up a spike. Below is a sample of 16 domain names from the first spike that lasts from May 11th to May 13 and consists of 1,500 domains.

ultra-outlinetowitnesstoday.info ultraoutline-towitnesstoday.info ultraoutlineto-witnesstoday[.]info ultraoutlinetowitness-today[.]info best-outlinetowitnesstoday[.]info bestoutline-towitnesstoday[.]info bestoutlineto-witnesstoday[.]info bestoutlinetowitness-today[.]info boss-outlinetowitnesstoday[.]info bossoutline-towitnesstoday[.]info bossoutlineto-witnesstoday[.]info bossoutlinetowitness-today[.]info cool-outlinetowitnesstoday[.]info cooloutline-towitnesstoday[.]info cooloutlineto-witnesstoday[.]info cooloutlinetowitness-today[.]info

When sorting the domains by length first, then alphabetically, the DDGA patterns usually group together very nicely and it is easy to spot the set of words that make up the dictionary used by the algorithm. Most importantly, none of these words correspond to any news events for the day they are registered. These are just random “word salad” domains.

Domain Blooms

Domain blooms start off similar to spikes. A word’s usage per day follows some baseline frequency, then after some event occurs rapidly increases to an outlier level. But unlike a spike, after a few days the number of domains per day either continues to increase, or holds steady over a period of time. After a while the number of such domains registered per day gradually drops back to its baseline level, or potentially a new baseline level that remains steady.

The quintessential example of a domain bloom is the COVID-19 bloom described in detail at the beginning of this post.

Blooms, especially those triggered by natural disasters are easy targets for threat actors. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, threat actors created hundreds of fraudulent fundraising and phishing domains pretending to be official domains for nonprofits and municipalities helping with the pandemic crisis.

Clustering Domain Blooms into Bouquets

One of the challenges during early COVID-19 was identifying other words that threat actors were taking advantage of when registering related malicious domains. Security Researchers had to guess at different words and look at their bloom graphs to see if they followed the same trend as “covid”, but it was a guessing game at first until a more algorithmic approach could be developed.

A domain bloom is really just a time series histogram, or count of occurrences over time. In data science this is called a vector, and for any given vector it is possible to search the vector space of all the known vectors to identify others that have very similar characteristics. In theory two blooms that start around the same time, have a similar shaped peak, and then end around the same time should be semantically related to each other.

To test this, a special type of machine learning algorithm called clustering was used which tries to group similar items together into clusters. To do this, bloom histogram vectors were generated for all words used in domain names registered during 2020. Then these bloom vectors were run through the clustering algorithm to generate groups of similar blooms.

Once the bloom clusters were generated, the cluster containing the bloom for “covid” was identified and the 5 most similar bloom vectors were pulled out. The blooms for these words are shown below:

Notice how not every bloom has the same magnitude as “covid”, but the general shape and duration are very similar.

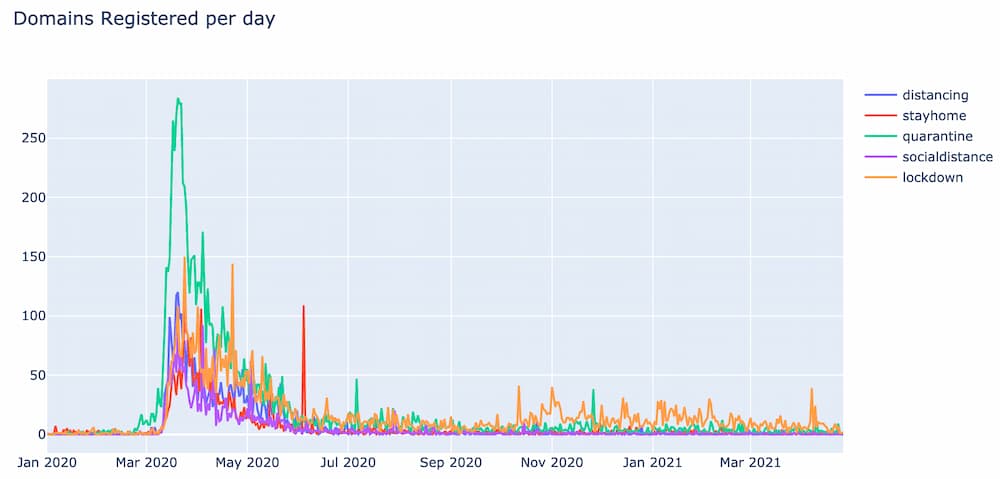

Other notable clusters identified during this analysis include this one around social distancing:

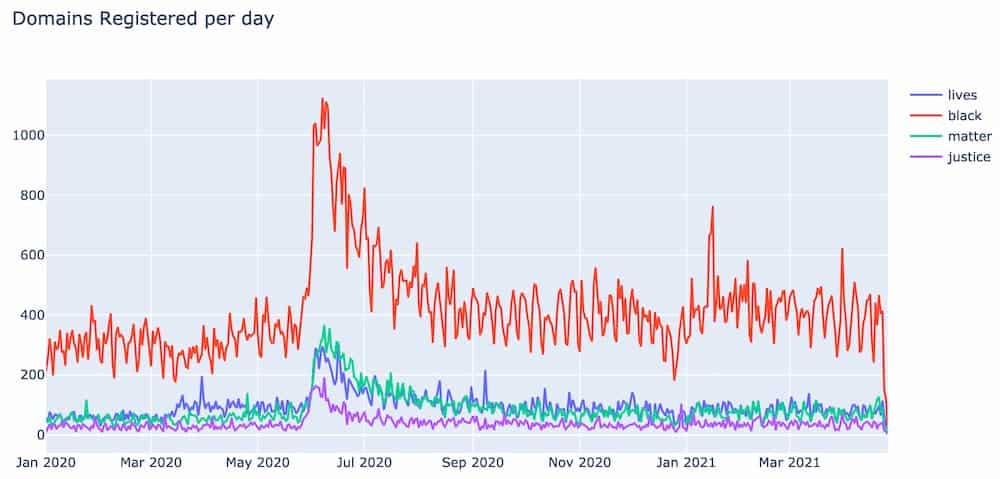

And this one around the Black Lives Matter movement:

Future Research

Not every major event is going to be as large of a focus for threat actors like COVID-19 was. Further research needs to be done to better categorize different types of blooms and spikes, identify the defining characteristics behind them, and better understand the motivations of the people who participated in registering these domains. Based on this learning we can better classify malicious domains that are registered in response to different events before they have the opportunity to become operational.

For an in depth analysis of some of the more notable domain spikes and blooms that occurred during 2020 take a look at The DomainTools Report: Spring 2021 Edition.