From Cybercrime to Political Repression, Shedding Light on the Iranian Cyber Army

Enjoy a guest blog written by Collin Anderson as a supplement to his published work “Iran’s Cyber Threat: Espionage, Sabotage, and Revenge“. Collin Anderson is a Washington, DC–based researcher focused on cybersecurity and internet regulation, with an emphasis on countries that restrict the free flow of information. Beginning in January 2018, he will be a fellow in the TechCongress Congressional Innovation Fellowship program. Prior to this fellowship, Anderson’s involvements have included working as a researcher at Measurement Lab, producing numerous publications on privacy and security, and advising several organizations focused on human rights and Iran.

*The following blog solely represents the views of Collin Anderson

On January 4, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace published “Iran’s Cyber Threat: Espionage, Sabotage, and Revenge,” an extensive report on Iranian cyber strategy over the past decade. One of the unique aspects of the publication is that it is informed by forensic research about actual attacks, largely those against human rights advocates and journalists. Through these primary sources, we were able to make evidence-based conclusions about the who, what, and why of Iran’s campaigns.

One of the most useful resources within this research been the domain data provided by DomainTools. As we describe in our report, Iranian hackers have often made fundamental mistakes that provide insights into their operations and origin, frequently found in domain records. A vivid example of how the DomainTools data was used comes from the attacks conducted by a group claiming to be the Iranian Cyber Army (ICA). In this post, I provide new insights into the commonly cited – and highly hyped – operation, including potentially identifying those behind the attacks based on historical Whois records.

Background

From December 2009 until June 2013, sites associated with Iran’s political opposition, Israeli businesses, independent Persian-language media, and international communications platforms were defaced by an actor claiming to be the ICA. The series of defacements has served as a public milestone in estimations of Iran’s ability to curtail domestic dissent and create economic harm through disruptive attacks. These attacks were used in order to demonstrate the power of the Iranian establishment at a moment of regime instability – specifically timed with politically-sensitive occasions during national anniversaries, protests, international tension or elections. These attacks also took on their own reputation, leading to bombastic claims about Iran’s capacities and involvement of foreign governments that continue until today.

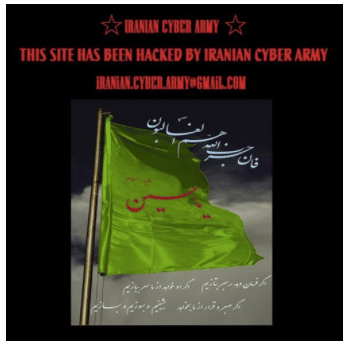

The Iranian Cyber Army campaigns were more sophisticated in their communications than in techniques, using well-designed graphics invoking Iranian nationalism, Hezbollah, and the Shi’a religion to convey political messages. This parallels later disruptive attacks: the campaigns engaged in state-aligned activities from actors within Iran have historically been conducted by ephemeral groups that were previously unknown and operate over a limited timeframe, maintaining a proxy actor quality. For example, when the site of Farsi1, a Persian-language satellite entertainment channel, was defaced on November 17, 2010 by actors claiming to be the ICA, the group posted images of Iranian flags and Kalashnikov rifles alongside the message “Rupert Murdoch, the Moby company, the Mohseni family, and the Zionists partners should know that they will take the wish to destroy the structure of Iranian families with them to the grave.”

There is consistent pattern across the high-profile defacements at the start the Iranian Cyber Army campaign. Sites were redirected to political propaganda after third parties gained access to accounts on domain name services and hosting providers. This access allowed the intruders to initiate transfers of the domain to other registrars, point to different name servers, or to change Whois records. Those actors behind the ICA defacement on at least one occasion called the victims claiming to be their hosting company, in order to gather the personal information necessary to convince the actual service provider of their assumed identity. In another instance, the actor would place a large order with sales representatives and offer a new credit card for the transaction, which after a few months would be used to verify their identity when they sought to change account passwords.

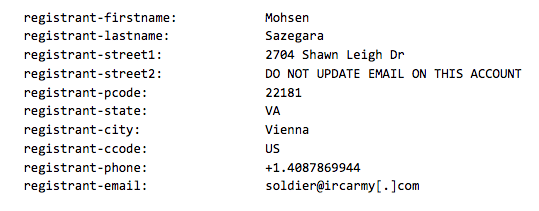

Evidence of the vectors of the compromises can be found in historical domain registration information of ICA defaced sites, such as within the site of Mohsen Sazegara, which when defaced was variably owned by “soldier@ircarmy[.]com” and “sazegara@ircaserver[.]com,” indicating that the actors had full control over the domain.

The first series of defacements under the ICA moniker ran from December 2009 to February 2011, in the middle of the Green Movement protests. These attacks targeting Iranian opposition movements and international technology companies, displaying pro-Islamic Republic messages addressing the political instability of the country at that time. Victims included Voice of America (VOA), Mowjcamp, Twitter, Baidu, Radio Zamaneh, Amir Kabir Newsletter, Jaras, and the MOBY Group.

These early defacements appeared primarily oriented toward a domestic audience, as its messages about foreign intervention and sedition as well as the country’s political affairs were written typically in the Persian language and addressed the Iranian public — even when threatening the foreign broadcasters MOBY Group and Radio Zamaneh – despite evidence that the perpetrator spoke English. The defacement of the Amir Kabir Newsletter, an opposition news source hosted outside the country but administered from within Iran, aligned with a multi-year history of attempts to identify and prosecute participants to the site.

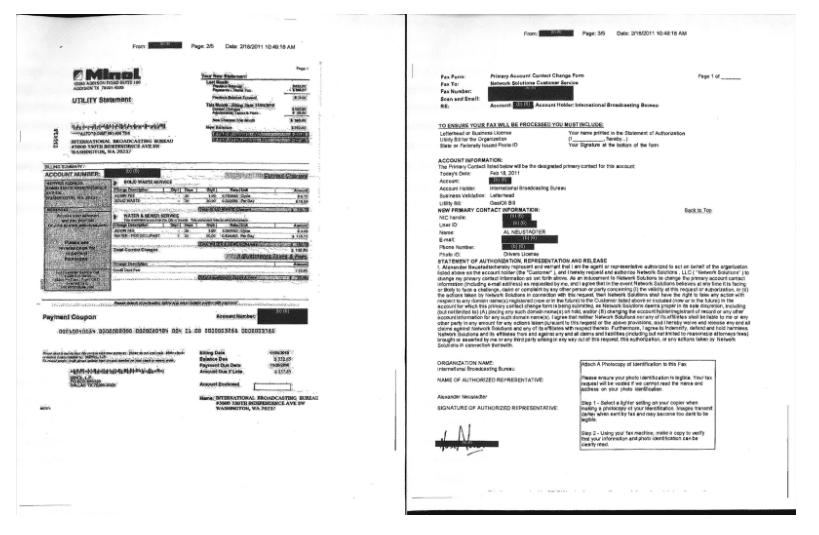

The Iranian Cyber Army’s defacements include the Voice of America (VOA), a U.S. government-funded international news broadcaster that has a Persian language service. Based on documents received through a Freedom of Information Act request, we found that the VOA was compromised through the social engineering of the agency’s domain registration provider Network Solutions.

On February 18, 2011, an individual posing as the IT administrator of the International Broadcasting Bureau’s (IBB, the program’s parent federal institution) sent a fax to Network Solutions to request the primary contact information be changed for the domain registrar account. In order to prove their identity as the account holder, the attacker sent an image of falsified identification and a bill from a Addison, Texas electrical company with the IBB name imposed on the document. Based on this successful change of contact information, Iranians gained control of VOA domains.

(In an email exchange with the FBI, DHS and US-CERT, BBG officials also express concerns that the incident was tied to previous intrusion attempts targeting the BBG in June 2010. One week after the ICA defacement, the BBG had also reported to US-CERT an incident where local accounts were accessed by unauthorized parties and used to exfiltrate data, which at the time was believed to be related to Iranian actors.)

Origin

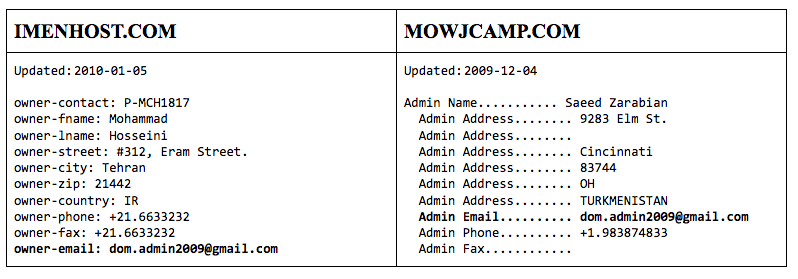

The ICA’s preferred method of disruption leaves a thorough trail in historical domain information. Nearly every defacement by the ICA is accompanied by indications that Whois and DNS records were modified around the time of the attack. For example, when the reformist website Mowjcamp was defaced by the ICA in December 2009, the Whois record’s email address was changed and the domain was transferred away from its registrar. This address and another directly associated with the ICA would be associated with a tangled set of identities implicated in financial crime that have not previously been disclosed, seeming to lead back to one person.

The ICA is Connected to a 2008 Anti-Sunni Defacement Incident

In response to the financial loss caused by the Iranian Cyber Army’s disruption of its services, Baidu filed a lawsuit against its registrar, Register.com, claiming gross negligence from their alleged failure to protect the company’s domains. The lawsuit and subsequent exchange between the litigants surfaced intimate details about how the domain was taken over by the ICA.

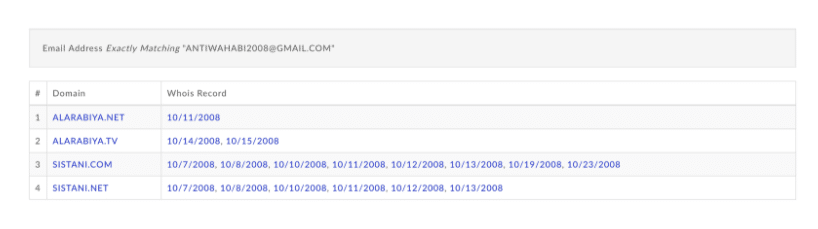

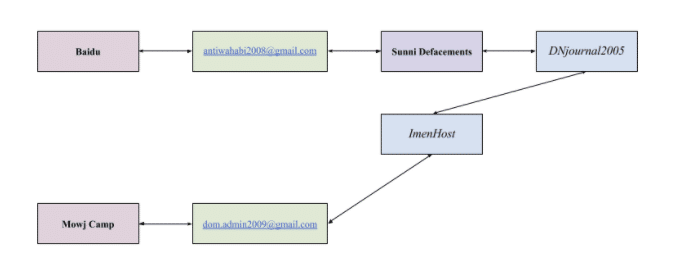

On January 11, 2010, an unnamed person contacted Register.com through the service’s online support to request a change in the administrative email address for Baidu’s account. The registrar’s customer service representative sent a security code to the email address on file to validate their identity before making the change, but did not confirm that the code offered by requester was the same as the one sent. The representative added the email address, which then allowed for the person to access Baidu’s account and change its DNS records to direct the domain to a server under their control. While there was no attribution to any specific individual in the lawsuit, the Baidu administrative contact information was changed to ‘antiwahabi2008@gmail[.]com.’ This email address exposes the tactics and actors behind components of the Iranian Cyber Army campaign, and implicates it in previous fraudulent activities leveraged for nationalist purposes.

Baidu’s counsel seized on Register.com’s failure to recognize the political undertones of the “anti-wahhabi” email address offered to the customer representative, a reference that reflects the deeper history of the actors involved in the seizure. The email address first surfaces in a series of defacements between Sunni and Shi’a groups that began after the Saudi-based “Group-XP” compromised hundreds of Shi’a sites, most notably replacing the site of Iraqi cleric Ayatollah Sistani with anti-Shi’a content. The “anti-wahhabi” email address is found in the domain name records of two of Sistani’s sites when they were reclaimed from Group-XP in October 7, 2008.

Concurrent to recovering the lost Sistani domains, the actor associated with the address continued with retaliatory defacements, appearing in the domain registration records of the Saudi-owned pan-Arab television al Arabiya when it was defaced on October 10.

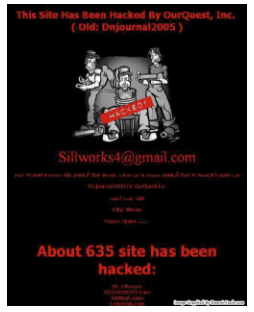

The Anti-Sunni Defacement Incidents Were Conducted by a “DNjournal2005” (later “OurQuest”)

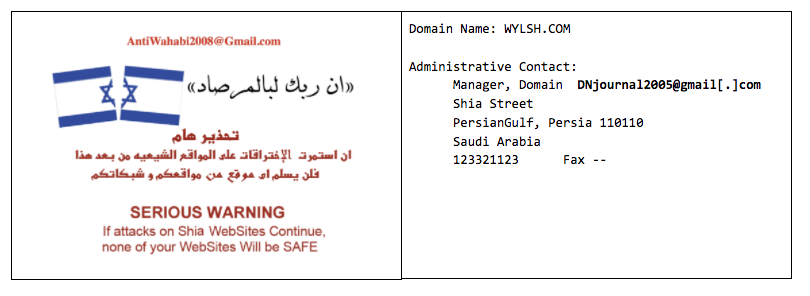

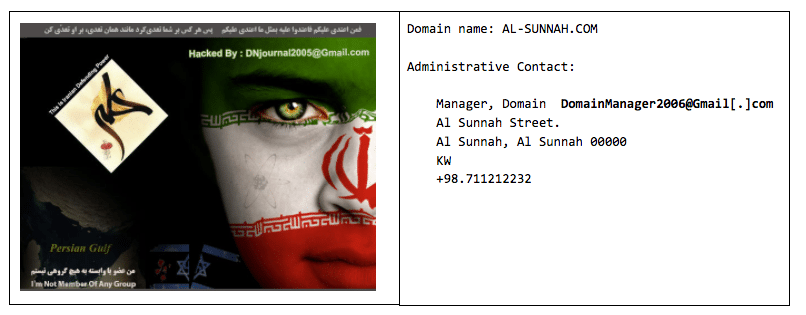

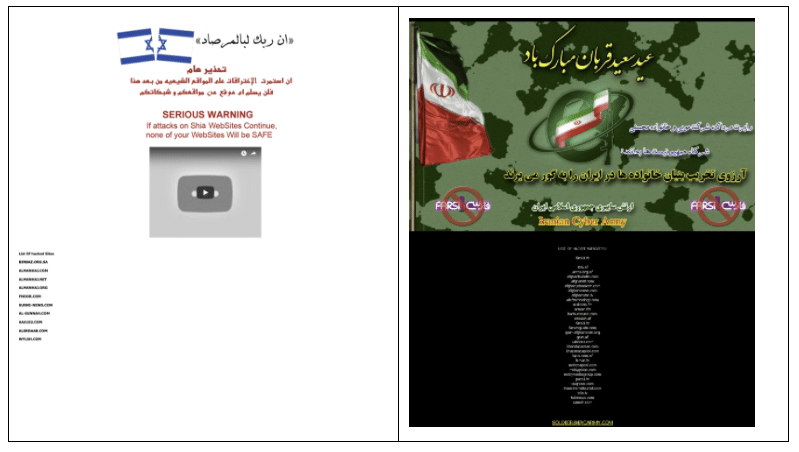

The anti-wahhabi address was then used alongside other aliases in the compromises of over a hundred Sunni religious domains, which vandalized the sites with anti-Israeli imagery and warning against further attacks in English and Arabic. These compromises included self-attribution within the defacement messages and domain name records. For example, in the defacement of wylsh.com the message provides attribution to the “anti-wahhabi” address with the domain records set to “Domain Manager” at “DNjournal2005@gmail[.]com.” These names and addresses were used interchangeably across defacements along with the alias DNjournal2005, which in some cases directly claims credit for the hijacks. This overlap indicates direct collaboration between DNjournal2005 and ICA-connected parties, and may in fact be the same actor (a fact noticed by an anonymous Persian-language blogger).

Sunni Defacements Emails:

- DNjournal2005@gmail[.]com

- hacker.web9@gmail[.]com

- antiwahabi2008@gmail[.]com

- domainmanager2006@gmail[.]com

Additionally, during this anti-Sunni campaign there was a stylistic overlap with the ICA: the attackers posted the full list of compromised sites on their defacement messages to brag about their accomplishment, similar to the pattern under of the early ICA defacements of the Moby Group, Radio Zamaneh, and Voice of America.

DNjournal2005 Has a History of Cybercrime

The personality and skill set demonstrated by DNjournal2005 align with those required to conducted the ICA attacks. DNjournal2005 and related aliases reveal an interesting campaign of cyber crime. Those behind the persona appear to have engaged in the commercial theft and extortion of hundreds of domain names since as early 2004 until at least September 2012, potentially incurring tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in illicit profit.

DNjournal2005’s alias originates from the compromise of the domain name sales industry publication DNJournal in 2005, wherein a person claiming to be from Iran threatened to disrupt other professional sites if they did not stop reporting on the individual’s commercial theft of domains. While DNjournal2005 did not address which theft they were responding to, one name that does arise is that of ImenHost, who had attempted to sell stolen domains on multiple occasions. From discussions on domain sales forums, it appears that theft of names by Iranians was an well known issue.

The defacement of domain speculation and sales industry communities continued over the year with DNjournal2005 leaving threatening messages about reporting stolen domains on other prominent sites, such as NamePros, SnapNames and DNForum. (“i hav 1 offer if dnforum give me 3000 dollar i leave the site and go away or else i never let dnforum in peace and always hack it so dnforum admin email me dnjournal2005@yahoo[.]com so i can talk you with detail”)

As with the ICA defacements, those early compromises occurred through the actor’s ability to deceive service providers into changing credentials. Public descriptions of the defacements of al Arabiya, Twitter, Voice of America and Baidu all fault their registrar and domain providers for handing over access to their accounts and allowing for the transfer of domains. The NamePros defacement occurred when DNjournal2005 was “able to successfully impersonate me to a support representative at my datacenter and convinced them enough to hand over my customer login and password.” When the F-Noor (fnoor.com) site was compromised in the anti-Sunni campaigns, the owner of the account took to their service provider’s support forums attributing the security failure to the company. Included in this exchange is an email sent from the individual who had taken control of the accounts – “centralemails@gmail[.]com” and DNjournal2005.

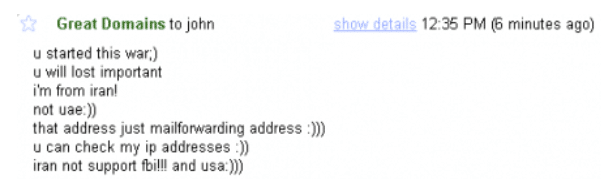

The ‘central emails’ and ‘anti-wahhabi’ email addresses from the seizure of Sunni sites appear in the compromise of a Czech entrepreneur’s domain names and Paypal accounts in November 2008, when a third-party gained access to their online accounts through providing their web host’s customer service with a fake passport. Personal information and more email addresses were exposed when the perpetrator then began to taunt the victim after the theft, a common behavior across incidents and aliases attributed to the actor.

Additional addresses in that compromise and in other overlapping incidents implicate DNjournal2005 in dozens of thefts conducted using:

- greatdomains2008@gmail[.]com

- sillworks4@gmail[.]com – used against persianwhois[.]com, used against direction[.]com

- stillworks20@gmail[.]com – used against sweets[.]com

- domainmanager2006@gmail[.]com – an email that also appears in several anti-Sunni defacements, used against story[.]com

Reinforcing the consistent personality, on the defacement of PersianWhois, an Iranian tech company, the attacker wrote mockingly: “instead of these childish games and instead of doing security, go work and make money.” Elsewhere he taunted another potential victim after being caught attempting to sell stolen domains:

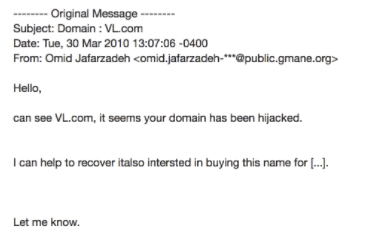

The actor behind the thefts was primarily focused on domains that were two and three letters long, or common English words, targeted due to their high market value. Documentation of the strategies of the seizures can be found in domain name communities as victims sought to determine how their important assets were lost. In March 2010, concurrent to the ICA campaign, the domain “vl.com” was briefly stolen through compromise of its owner’s Dreamhost account, which was accomplished through impersonation of the owner on the hosting provider’s online support service. This set up a struggle between the owner and the hijacker as the latter attempted to secure the domain through playing companies against each other. Once again, this incident mirrors the tactic seen in the Baidu case affiliated with the ICA.

Moreover, the direct overlap between the theft of Sunni domains and commercially valuable domains can be found with the “domainmanager2006” address.

The actor would compromise accounts of domains, transfer them to another provider and then either extort the previous owner or sell them on the speculation market. Reports on stolen names such as “vl.com” and “married.com,” owned by Marriage Ministries International, put the valuation of the theft of some of the domains as high as $100,000 alone, and commonly in the tens of thousands. The actor also appeared to rely on Iran related escrow services (Rialex appears in multiple Whois records for DNjournal2005-linked thefts) and potentially unwitting partners outside Iran to move money.

DNjournal2005 Appears to be a Omid Jafarzadeh

The consistent use of a set of personas and tactics indicates that there may have been a limited number of actors involved with the early Iranian Cyber Army defacements and the DNjournal2005 thefts – potentially only one individual, an Omid Jafarzadeh in Shiraz, Iran.

When the Persian language blogging platform IranBlog was vandalized in November 2007, it announced that DNjournal2005 had changed his alias to “OurQuest, Inc.” and provided an contact email address seen in other thefts. The defacement also provides a first name of Omid and their location in Shiraz, Iran. The change of email in Whois records during this time once again suggests IranBlog was compromised through its domain services, and the suspicious address (roshdnet@hotmail[.]com) again can be found in a dozen other domains of significant commercial value. Finally, similar to the ICA and anti-Sunni hacks, the IranBlog message displays a list of compromised domains.

A profile on the Iranian social networking site Cloob for “OurQuestInc,” claimed an interest in “Selling Top Domains” and “Mostaghel AZ Lahaze $$ Kariiiii” (financial independence), with a listed residence of Sattarkhan Blvd. in the city of Shiraz. (Although we note discrepancies in noted ages across communications. In the DNJournal defacement, the intruder claimed to be 16/17 years old in 2006 and from Iran, however, OurQuestInc’s Cloob profile claimed to be slightly older.)

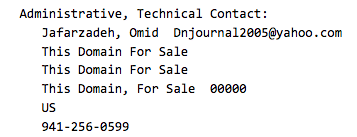

OurQuestInc and Sattarkhan Blvd both appear in frequently registration for domains stolen in tandem with DNjournal2005 accounts. In the registration for Arcade.Org, the OurQuestInc related email address lists a “Omid Jafarzadeh” and Sattarkhan Blvd. Jafarzadeh was was implicated in the attempted theft of vl.com on a public mailing list and appears as the contact name for DNjournal2005’s theft of “salesline.com,” “infinitecasino.com” and “polymeter.com,” among others.

DNjournal2005 used the email DNjournal2005@yahoo[.]com when stealing domains; seven of these domains in early 2006 have a registration name of “Omid Jafarzadeh” with the address “This Domain For Sale” that is common for other aliases.

Domain infinitecasino.com on February 18, 2006:

Jafarzadeh’s Other Aliases Appear in Another ICA Defacement

It is impossible to tell whether Jafarzadeh acted alone, but a consistent personality and recurrent traits appear across the DNjournal2005 and OurQuest Inc alias, such as his location and attitude. Jafarzadeh seems to have maintained a number of identities, including potentially “ImenHost, Inc” and “[email protected],” the former implicated in further commercial thefts. The latter was responsible for the brief theft of domains related to Balatarin, the Iranian “Feminist School,” and pornography, sites singled out by the Iranian government’s censorship regime, as well as high-value domains. Jafarzadeh and Sattarkhan Blvd lists the administrator as imenhost@gmail[.]com for IranTeacher.com and Vastertools.com, and ImenHost appears with gaurddragon.com for the ownership of weatherposition.com briefly in 2009. OurQuestInc also appears at the contact at certain times for ImenHost.

A username of “ImenHost” used the Jafarzadeh-linked email address iranwebmaster2003@yahoo[.]com when attempting to sell domains in 2005; several dozen domains contain the name Omid and his email address, as early as April 2004 (ADABHONAR[.]COM) and as late as August 2008 (PASARGAD[.]US). Moreover, ImenHost used the email address omidjafarzadeh3000@yahoo[.]com when attempting to sell domains in 2004. As with everything else tied to Jafarzadeh, the alias also appears linked to the theft of commercially valuable domains.

In January 2010, ImenHost was briefly registered to “dom.admin2009@gmail[.]com.” This creates an additional link between Jafarzadeh and the ICA, as the email appeared in domain for MOWJCAMP.COM when it was defaced by the ICA.

Conclusion

The Iranian Cyber Army has been implicated in a wide range of compromises and disruptions of foreign infrastructure beyond the first series of defacement. Little was left by the original actors to authenticate the assertions made by groups claiming to be the ICA in later incidents. Across the episodes of ICA defacements, the evolutions in the campaigns’ approach, language and imagery demonstrates shifts within the “group.” Dramatic changes in exploitation vectors and political messaging strategies suggest that rather than being a consistent set of actors, the participants changed over time. During lulls between the phases of activity, the domains and resources maintained in the name of the ICA frequently lapsed and were renewed by others unrelated to the group, or changed between engagements. On defacements messages and in records such as Zone-H, the ICA’s messaging and personality shifted over time, from changing attribution (“Iranian Cyber Army” to “Ir.CA” to “iCA”), differing logos and graphics, inconsistent contact information (including a Gmail and GMX addresses), and failures to renew domain names (using at times “IrcArmy.com,” “CyberArmyOfIran.com,” and “IRCAServer.com”). These inconsistencies across discrete campaigns may indicate that the ICA was a brand franchised by different members across time, rather than a fixed set of actors, similar to Anonymous, without precluding the possibility of external or community coordination.

The financially-motivated thefts by Jafarzadeh all match the pattern of tactics and techniques used in first activities conducted by the Iranian Cyber Army, and the information that connects the campaigns across different incidents and over time. None of the ICA defacements required substantial technical sophistication, only weakness on the part of those targeted or the several other companies that the sites relied on to function. The ICA and Jafarzadeh were skilled at social engineering, not technical breaches of infrastructure. Any actor with dedicated time and attention, a grasp of the English-language, and a few techniques refined from experiences would have naturally gained access to sufficiently high-profile infrastructure to make statements.

The overlap between the ICA and commercial theft reinforce that systemic insecurities used in fraud can one day be used to threaten dissidents and foreign governments the next. Moreover, the repeated ties to Jafarzadeh demonstrate the power of one individual to exercise an outsized image of destructive capacity, and portray a country such as Iran as an cyberpower. Finally, the way that these ties were found through the historical records available through DomainTools is also illustrative of how researchers can use technical indicators as primary source material to more accurately document important details and make sense of attacks.