The Devil’s in the Details: SUNBURST Attribution

Background

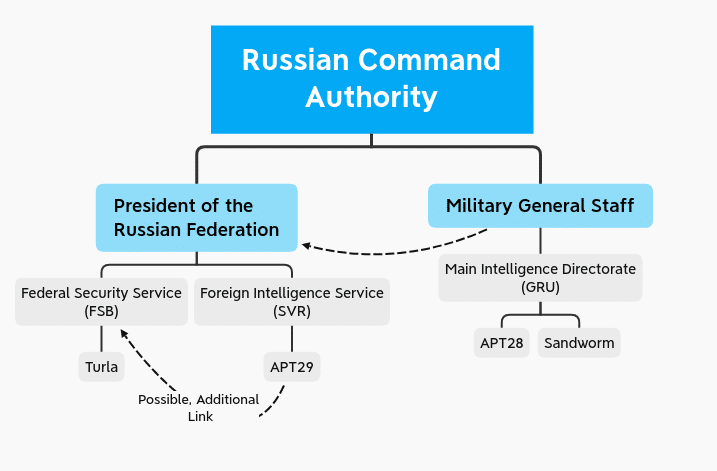

Since initial disclosure in December 2020, the supply chain incident involving SolarWinds was linked in media reports to Russian intelligence entities, specifically Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR). As previously reported by DomainTools, although it appears multiple government sources link the event to SVR, this has resulted in a type of “transitive” attribution to link the activity to APT29, also known as Cozy Bear or YTTRIUM, the only commercially-identified threat actor names linked to Russia’s SVR.

Yet none of the commercial entities responding to events linked SUNBURST malware (or the wider Solorigate campaign), including FireEye, Microsoft, Volexity, and CrowdStrike, to SVR-associated APT29. Subsequent US government information on the event, from two Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) reports which included no significant attribution statements, to more recent government statements which only assess that the responsible entity is “likely Russian in origin” and also do not make the SVR claim. Initially, the only substantive links to Russian intelligence activity (and SVR specifically) were through leaks to media organizations, with private security companies largely sitting the discussion out.

This changed on 11 January 2021 with a report published by Kaspersky. The report identified functional and code-level overlaps between the SUNBURST backdoor associated with the SolarWinds infection vector and .NET-based backdoor malware referred to as Kazuar. Of note, Kazuar activity (which according to Kasperksy’s analysis continued through December 2020) is only associated with one threat group: an entity referred to as Turla. The implication from Kaspersky’s nuanced analysis is the possibility that SUNBURST activity and the Turla group are potentially (although far from conclusively, as noted by Kaspersky researchers) related.

Who is Turla?

Turla—also referred to as Snake, Uroburos, Venomous Bear, and Waterbug—is assessed to have been active in some form since as early as 2004. Known for targeting political, military, and certain sensitive technology sectors, the group is frequently associated with complex toolsets and audacious operations such as co-opting satellite internet links for Command and Control (C2) activity.

Turla is associated with Russian interests and activity but has never been the subject of a detailed report or authoritative document, such as a US Department of Justice (DoJ) indictment or similar primary source. Several entities, such as Estonian and Czech intelligence services, link Turla with Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB). However, despite multiple historical reports covering Turla activity from the US National Security Agency (NSA), CISA (then US-CERT) and the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), such entities only highlight that Turla is “widely reported to be associated with Russian actors,” avoiding any specific attribution.

While Estonian and Czech assessments cannot be completely discounted, it is notable that the US and UK governments—which have previously performed very specific attribution on other Russia-linked entities such as APT28 and Sandworm—abstain from similar assessments. While a Turla-FSB link is possible, at this time it is not as solid as similar assessments such as GRU links to APT28 and Sandworm.

Examining Possibilities

The most direct conclusion from Kaspersky’s analysis is that SUNBURST is linked to Turla operations, which would potentially associate the campaign with Russia’s FSB and not SVR. However, Kaspersky analysts in both their reporting and social media communication emphasize that while a SUNBURST-Turla link is possible, this is hardly the only possibility available. Multiple possibilities exist, which will be discussed below.

Turla Involvement

The first and most direct possibility is that Turla is indeed responsible for the SolarWinds and related intrusion activity. This would provide a very simple and efficient explanation for Kaspersky’s findings. Yet, there are problems with this assessment and other data points which do not support the conclusion.

For one, there is the FSB (likely, although not definitively, associated with Turla) versus SVR (indicated by multiple direct sources, including some available to DomainTools, as likely responsible) distinction. While Turla concrete attribution is hardly complete or definitive, unlike for other Russia-linked threat actors, the consensus of what limited claims exist focus on FSB. Meanwhile, multiple sources continue to emphasize that SVR is ultimately responsible for SUNBURST and related activity. The possibility of a single actor moving among organizations will be discussed below, but as a one-to-one mapping SUNBURST-Turla linkage seems problematic if we trust multiple government and confidential sources.

Admittedly, the sources in question are not without fault or criticism. The Estonian and Czech reports linking Turla to FSB cite no evidence of significance and these claims are not backed up in any other reporting. At the same time, SVR involvement in SUNBURST is based on no public, documented reporting, but instead derives from leaks to the media and private (if trusted) conversations. The only public statements by US government entities so far have emphasized a “likely” Russian nexus without naming a specific entity or alluding to any industry threat actors.

It is worth noting that Turla is associated with complex, high operational security intrusions since the group’s initial discovery. As such, a multi-staged, stealthy intrusion such as SUNBURST and related activity would appear to align with Turla’s operations. However, follow-on actions in victim environments, including extensive use of credential capture and replay as well as customized Cobalt Strike functionality as documented by FireEye and Microsoft, align with behaviors associated with APT29. From a pure tradecraft perspective then, the evidence is inconclusive.

Contracted Actor Responsible

One possibility, which may explain the code overlap with Turla-linked tooling for a different actor, would be a shared, contracted developer resource supporting two different entities. In this scenario, malware developer resources are not dedicated to or housed within a single entity but instead reside as an external service provided to the actual intrusion set.

If this were used, malware sample code-level and function-level overlaps would be artifacts of common developer environments and tendencies and would be unrelated to the actual actors using the tools. Malware-centric threat analysis faces pitfalls and traps in that the analyzed object represents an artifact or tool used by an adversary, rather than necessarily an item inherent to the adversary itself.

While a malware-focused threat intelligence approach most obviously faces issues with tools that are publicly available, open source, or otherwise non-exclusive to specific threat actors, division of labor in cyber operations means overlaps may occur in otherwise “non-public” tooling as well. Under these circumstances, a single developer or developer resource is relied upon or hired to support tool development by multiple parties. Based on coding “quirks” and other tendencies, subtle similarities appear within tools not directly or critically related to tool functionality.

Unfortunately, this type of attribution is incredibly difficult to prove without having significant insight into the operations and resource management of threat actors. Yet we cannot discount the existence of malicious tool creators for hire—or even the possibility of shared “digital quartermaster” resources supporting disparate teams. If this were true, an overlap with Turla would be an artifact of such an arrangement while the perpetrators of Solorigate could represent another operational entity entirely.

Joint Operation

An intriguing scenario surrounding the Solorigate activity in general and SUNBURST deployment in particular would be a joint or divided operation. In this scenario, the cyber kill chain is not executed or managed by a monolithic entity. Instead, different elements are operationally responsible for different stages of operations, with separate “access,” “intrusion,” and “execution” teams taking on specific roles.

If this were to hold as valid, Turla-linked capabilities in SUNBURST may be an artifact of Turla—a known, capable intrusion actor—having responsibility for initial access operations to victim networks. Meanwhile, follow-on exploitation and lateral movement are handed over to another team, with its own methods, tools, and tradecraft for carrying out operations.

As described previously, SUNBURST appears to at least superficially resemble Turla-linked capabilities and operations, while post-exploitation activity seems more closely linked to behaviors associated with APT29. Such divergence may not be an anomaly, but actually represent two distinct teams involved in the same operation.

While limited, public information links these activities to two distinct parts of Russia’s intelligence community (FSB and SVR, respectively), the possibility of these two organizations working together or in complementary fashion may be unlikely, but not outside the bounds of possibility. Both derive from the same ancestor organization—the Committee for State Security (KGB)—and have identical reporting and chain of command structures under the Russian President’s Council. That these organizations—typically divided between mostly (although not exclusively) internal (FSB) and external (SVR) operations—might collaborate makes more sense than either organization working in concert with Russia’s other major intelligence entity, the military’s Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU).

Although provocative, this theory would require significantly greater amounts of evidence to support it. Additional tools or capabilities representing initial access vectors, similar to SUNBURST, and further details on follow-on capabilities and exploitation would be necessary to have adequate information to justify delineating operations between distinct entities. Nonetheless, we cannot simply dismiss this as a possibility, and we as cyber threat intelligence analysts should be wary of assuming all operations are “unitary” in nature instead of composite operations divided among specialist teams.

“False Flag” Operation

The overlaps with Turla-associated functionality in SUNBURST may represent an effort by the threat actor to throw off attribution through a “false flag,” misdirection operation. As documented by other researchers, Solorigate and related events may map to completely different threats previously noted for highly-targeted supply chain activities.

Yet on closer examination, although still possible, this seems less probable. For one, SUNBURST and related activity operated at a relatively obscure level of program functionality or tendencies such that it took a third-party, not known to be engaged in any active investigations in victim environments, to make the connection through very detailed malware reverse engineering. While one could claim such efforts are part of an exceptionally savvy, operationally secure operation, this level of effort and the non-obvious similarities (compared to, say, the ultimately obvious “tells” embedded within the Olympic Destroyer event) would appear to indicate otherwise. The ability to make this (still tenuous) link to Turla relies upon recognition of non-obvious, technically obtuse overlaps between SUNBURST and Kazuar code, making this a very difficult and potentially unreliable mechanism to divert blame to another party.

Second, while the quality of existing sourcing has already been described as less than ideal with respect to Solorigate attribution, it remains that multiple US government agencies have publicly declared that Russia-linked entities are “likely” responsible for the event. While we may decry lack of additional detail and technical indicators making this case more complete, that such agencies would go public with such a proclamation in itself indicates a level of confidence in the assessment which is probably higher than the “likely” modifier attached to it.

Certainly a “we’re from the government, trust us” stance is problematic and less than ideal, but overall there are no significant examples of public US attribution statements ultimately being proved completely or disastrously wrong. In fact, previous work—such as that identifying Turla as having compromised APT34 to further Turla campaigns—indicates the US and UK governments are able to unpack false flag events when they occur. Therefore, although less than ideal, the declaration from CISA, NSA, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) should give us as analysts pause before we engage in equally unfounded “whataboutism” in declaring that SUNBURST may be a false flag operation executed by an entity such as APT41.

Coincidence

Finally, the items in question identified by Kaspersky may ultimately be the result of coincidence. Programmatic overlaps may be the result of developers having similar instructors, viewing the same support forums, or arriving at similar conclusions to similar problems. Short of additional evidence supporting a link to Turla for SUNBURST development, we as analysts may remain with only this perspective as a means to explain why SUNBURST overlapped with Kazuar in subtle, but nonetheless noticeable to the trained eye, ways.

Although disappointing and unexciting, this explanation may prove to be the most likely reason for such overlaps to occur. Yet the underlying reasons giving rise to these coincidences—programming similarities and other oddities—may indicate similar backgrounds or developer methodologies between Kazuar and SUNBURST even if operationally the items are used by completely distinct entities. Such an insight may cast an interesting light upon malware developer tendencies and similar observables, even if this does not lend any further detail to who is responsible for SUNBURST’s deployment.

Conclusion

Investigation into the Solorigate activity, including its components such as SUNBURST and recently-disclosed SUNSPOT, remains ongoing. As noted by researchers from Kaspersky, more evidence is required before linking the activity to any known, tracked entity, although the technical analysis provided indicates subtle, tantalizing links to historical actors. Nonetheless, we as cyber threat analysts and network defenders must remain skeptical, and process alternatives to the identified activity to ensure we do not engage in assumptions or similar intellectual shortcuts that may disadvantage future investigations.

Overall, the process of specific attribution remains an exceptionally difficult task when dealing with less than complete information or viewing an intrusion from an external perspective. While the Solorigate activity and components such as SUNBURST and SUNSPOT are items of intense scrutiny and interest at this time, accurate attribution may depend on additional information gathering and leveraging non-cyber sources to clear up certain doubts and remaining questions. As a result, although this is frustrating on many levels to CTI professionals, we likely will be waiting months, if not years, before identifying additional information necessary to learn who is precisely responsible for this event within the current landscape of threat actors. This is not to say that such a task is impossible, but rather to emphasize the need for patience, dispassionate analysis, and continual information gathering to ensure accuracy.